Basic Questions about Brenner and the Profit Rate

An Attempt at Self-Education

It is difficult to think of a currently active intellectual who has had more impact on the way leftists (and especially Marxists) think about political economy than Robert Brenner, who must surely be counted among the most important living historians. Brenner’s arguments about the profitability of post-1945 capitalism are widely influential and have recently served him as the basis for a pair of essays with controversial conclusions. As a preliminary to thinking about the questions raised by those essays, I first wanted to lay out some basic points which I hope are both uncontroversial and clarifying.

Why do Profits Matter?

According to Brenner, profits matter because investment matters: “The profit rate is the key to the economy's health because it is the key to the growth of investment.” Investment matters for two reasons: first, investment demand is the most important element of aggregate demand, and aggregate demand determines overall employment and output; second, because investment leads to productivity increases and therefore to an increase in potential output. In Brenner’s words:

Leaving aside the government, I see the growth of demand in the private sector as basically resulting from the growth of investment, dependent upon the profit rate. The growth of investment creates both the growth of employment and, by way of the growth of employment and the growth of productivity, the growth of real wages. So, the growth of investment creates the growth of demand both for capital goods - plant and equipment - and for consumer goods.

Given the importance of investment, how are profits the key to investment? Brenner cites two mechanisms. First, retained earnings are an important source of financing for investment: “Higher profit rates make for higher available surpluses.” Second, profit signals provide the motive for new investment: “companies have little choice but to regard the realized rate of profit as the best available indicator of the investment climate, the expected rate of profit.”

There is almost nothing here that Kalecki or Keynes would object to. They might point out that investment can be financed externally, not just by retained earnings, but profit expectations still matter here because creditors will generally expect to be paid back some day. The only really significant difference I can see here is Brenner’s identification of profits with “the profit rate.” This identification is far from universal, for reasons which are pretty clear if you think about the two reasons that profit matters in this story. The first was that profits provide an important source of financing for investment. It is not at all obvious why the profit rate (for Brenner, the economy-wide ratio of profits to the capital stock) is the salient metric here. What matters is the ratio of the mass of profits to the cost of desired investments. Even leaving aside the question of credit, it is not clear how the ratio of profits to the capital stock could constitute the binding financial constraint.

It is also unclear why the profit rate (defined as Brenner defines it) is the most relevant signal guiding actual investment decisions. Empirically, is there any evidence of a firm making an investment decision based on the economy-wide ratio of profits to the capital stock? Theoretically, why would the size of capital stock be the relevant denominator, rather than the ratio of returns to the cost of the new investment? In an economy with a large capital stock, and therefore a low profit rate, why wouldn’t a capitalist still invest if he expects a large enough return relative to the cost of his new investment?

Which Way Does the Line Go?

For the sake of argument, bracket the above questions about the relevance of the profit rate. Bracket also the many objections that other Marxists have to Brenner’s way of defining and measuring the profit rate.[1] Accepting Brenner’s concept, what is the actual shape of the profit rate? To be absolutely certain that the concept used is the same one, start with a graph from Brenner’s Economics of Global Turbulence:

The dotted line represents the broadest profit rate, the one calculated for the entire private economy. What jumps out it is that no dramatic decline is really evident at all. From the peak of the late 1960s there is certainly a falling trend into the mid-1980s, but thereafter the rate recovers, returning to levels that would not be out of place in the “golden age” even if never regaining its highest-ever peak.

The golden age peak of manufacturing profits, likewise never regained on this measure, is more dramatic, but there is no clear argument for why manufacturing profits should be especially important given that manufacturing currently accounts for only 11% of value added in the U.S. economy. You might imagine that the argument would be that the manufacturing profit rate somehow has the power to throw off the economy-wide profit rate, but if that were the case the result should be clear in the economy-wide profit rate. If anything, this graph shows manufacturing profits applying slight upward pressure to the overall rate.

We get a little more of the chronological picture in this graph, from the 2009 prologue to the Spanish edition of EGT. This graph shows profit rates for three countries: the U.S. is the lighter colored line studded with diamonds:

More recent figures of profits relative to the capital stock have been produced by Doug Henwood and Anusar Farooqui. I am a real amateur at this sort of thing, but I used FRED to construct what I believe is a comparable measure extending nearly into the present:

In none of these graphs is it obvious that an epochal decline is in train. Instead, it looks like the 1960s (and to a lesser extent 1950s) saw exceptionally strong profit rates, and that since then there has been a lower but basically stable cyclical pattern. If, as we saw above, profits matter in part as a source of financing, there is no evidence that firms have now run out of money to invest (again, even leaving aside the by-now familiar phenomenon of external financing for investment). In fact, Brenner’s recent writings lament the widespread tendency of corporations to use their money for dividends, stock buybacks, and executive compensation. The very fact that the corporations are able (through a combination of earnings and borrowing) to money for these purposes means that they have money they could be using for investments, which suggest the rate of profit is not acting as a financing constraint on investment.

So What?

I think there are two reasons it’s worth thinking this stuff through. The first is that within certain currents of the left, it has become common to use the authority of Brenner’s argument about profits as the grounds for extraordinarily strong claims about the future of capitalism and the feasibility of various political projects. In perhaps the most extreme example, Joshua Clover argued that the “collapse of profitability” made it literally impossible for California to build high-speed rail.[2] Naturally, Brenner himself is not responsible for the use other people make of his work. But in Brenner’s own writings, the supposed collapse of profitability is also cited as apodictic evidence of the impossibility of various reformist politics and even a “transition from capitalism (back) to feudalism.” For these arguments to be complete, we need an explanation of why the profit rate is the relevant indicator (for either the availability of investment financing or the inducement to invest), why profits divided by the capital stock is the right way to think about the profit rate, and why the trend actually indicated even by Brenner’s own metric provides grounds for such dramatic conclusions.

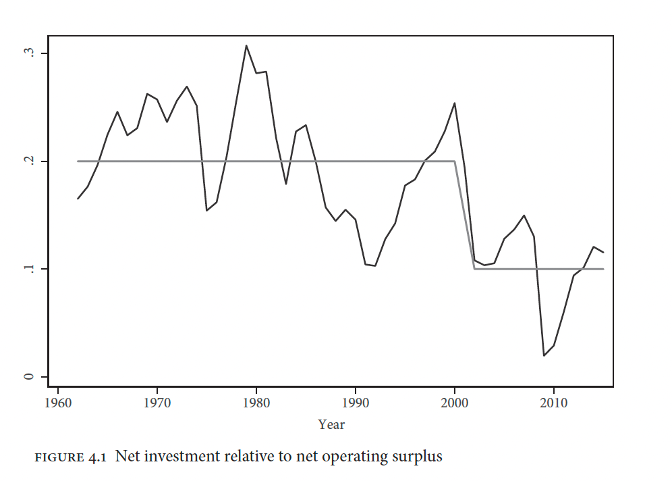

The second reason I think this is interesting is that, whatever is going on with profits, Brenner is correct (though hardly unique in pointing out) that fixed investment in the U.S. has been weak for decades. I don’t think anyone seriously disputes this, though I’d be interested to know if that argument has in fact been made somewhere. The question therefore is whether to think of weak investment as the predictable result of a falling profit rate, or as the somewhat puzzling failure of investment to behave as it “should” given the level of profits. For an example of the latter approach, consider this figure from Thomas Philippon, which shows the falling ratio of net investment to net operating surplus (the latter is another measure of profits):

There has been plenty written from this perspective (see, for example, J.W. Mason and Engelbert Stockhammer). The most common explanation, is that since the 1980s the shareholder revolution has meant that activist shareholders have both the desire and the capacity to enforce a low investment, high cash payout model onto corporate managers. This is clearly a big part of the story (recall that even Brenner complains about shareholder preference for buybacks) but I also don’t think we have the whole story here either—a topic I will hopefully return in another post.

[1] The most clarifying response I received on this point came from Jasper Bernes, who said that a Marxist measurement of the profit rate cannot do as Brenner does, namely make use of the data as presented in the BEA’s national income accounts. The data can be transformed to better fit Marxist categories (specifically, to separate productive capital from unproductive) but “the problems are vast and perhaps insuperable (given available data).” I can imagine, in the abstract, how a transformation of the data would provide a profit rate that might provide insight into the underlying health of the economy as a whole; it is harder to see how such difficult if not impossible to observe trends would influence the investment decisions made by capitalists. In any case, I have not gone deeply into these questions, over which an enormous amount of ink (and probably some blood) has been spilled.

[2] Interestingly, Clover linked to a post on the Brenner thesis by Anusar Farooqui which actually rejects the view “that there was a ‘deep fall, and failure to recover, of the economy-wide rate of profit.’”

The role of demand surely big part of the answer? Extent of demand growth determines how much firms willing to reinvest. Up through the 1970s you've got govt committed to sustaining demand, this starts to shift in the 80s, then you've got big credit boom in 90s. Lower investment-profit ratio from 2000s onwards reflects gradual/eventual slowdown of private (consumer) credit growth and govt not really stepping up to plate to compensate. Anwar Shaikh is really interesting on this (Capitalism, Ch. 15). He puts the investment-profit ratio at the heart of his understanding of macroeconomics, linking it to demand management and the generation of inflation (i.e. the investment-profit ratio as better alternative to Phillips Curve).

Huge fan for years - "The Bleak Left" was a favorite in my Jacobin reading group and inspired some of us to read Endnotes. I'm glad you started a Substack! Do you ever read Julius Krein? I think this article is a good theory on the disconnect between profit and investment.

https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2021/08/the-value-of-nothing-capital-versus-growth/

"These issues are even more significant, if somewhat less visible, in firms’ internal capital allocation decisions. In theory, firms should invest in a new project whenever the expected returns on the investment exceed the firm’s cost of capital. In practice, however, firms have maintained “hurdle rates” considerably above their cost of capital; multiple studies have shown that hurdle rates typically exceed firm cost of capital by up to 7.5 percent.16 Moreover, hurdle rates have largely remained constant at around 15 percent for decades despite falling interest rates (and thus lowered cost of capital) in recent years.17

From the standpoint of economic theory, this represents an irrational refusal to maximize profits. But with regard to maximizing equity value, it is an eminently rational strategy. Lowering hurdle rates would mean investing in projects that might increase earnings, but which would likely degrade earnings quality. In other words, metrics like return on assets would deteriorate and valuation multiples would probably fall. Avoiding such investments—and instead returning cash to shareholders to further prop up valuations—becomes a preferable approach to maximizing shareholder value even if it forgoes substantial profit opportunities. But if the link between shareholder value and profits is severed, then the justifications for shareholder primacy—and much else in economic theory—collapse.18"