Weapons of the Week #13: When Walter Reuther (Almost) Met Paul Nitze

A trip into the Cold War archives, to avoid the unbearable present.

One reason this newsletter has not appeared as regularly as intended is that I find the news unbearably depressing. But I like writing the newsletter, and many of you have been so incredibly generous as to sign up for it, so I need to find a way around that problem. One possibility that occurs to me is to write more about the history of the military-industrial complex. Sometimes it’s easier to focus on even the most horrible events of the past, not just because of their distance but because we have some sense of how things turned out, for better and (so often) for worse. On more than one level, it’s a question of avoiding the excruciating feeling of powerlessness. Since we know, or can know, what happened, the historian doesn’t relate to the object of study as an unknown force bearing down as he watches helplessly. More than that, he is allowed some feeling—no doubt illusory and compensatory—of control. He gets to pick his evidence, order it as he likes, and add commentary, as if it matters what Tim Barker says about Paul Nitze or Dean Acheson or Mao Zedong.

I am currently in the process of revising my dissertation for publication as a book (if all goes well, look out for it in 2026). This has involved going back through archival research I did 6 or 7 years ago, which can feel overwhelming. Most of my Apple Photos looks like this:

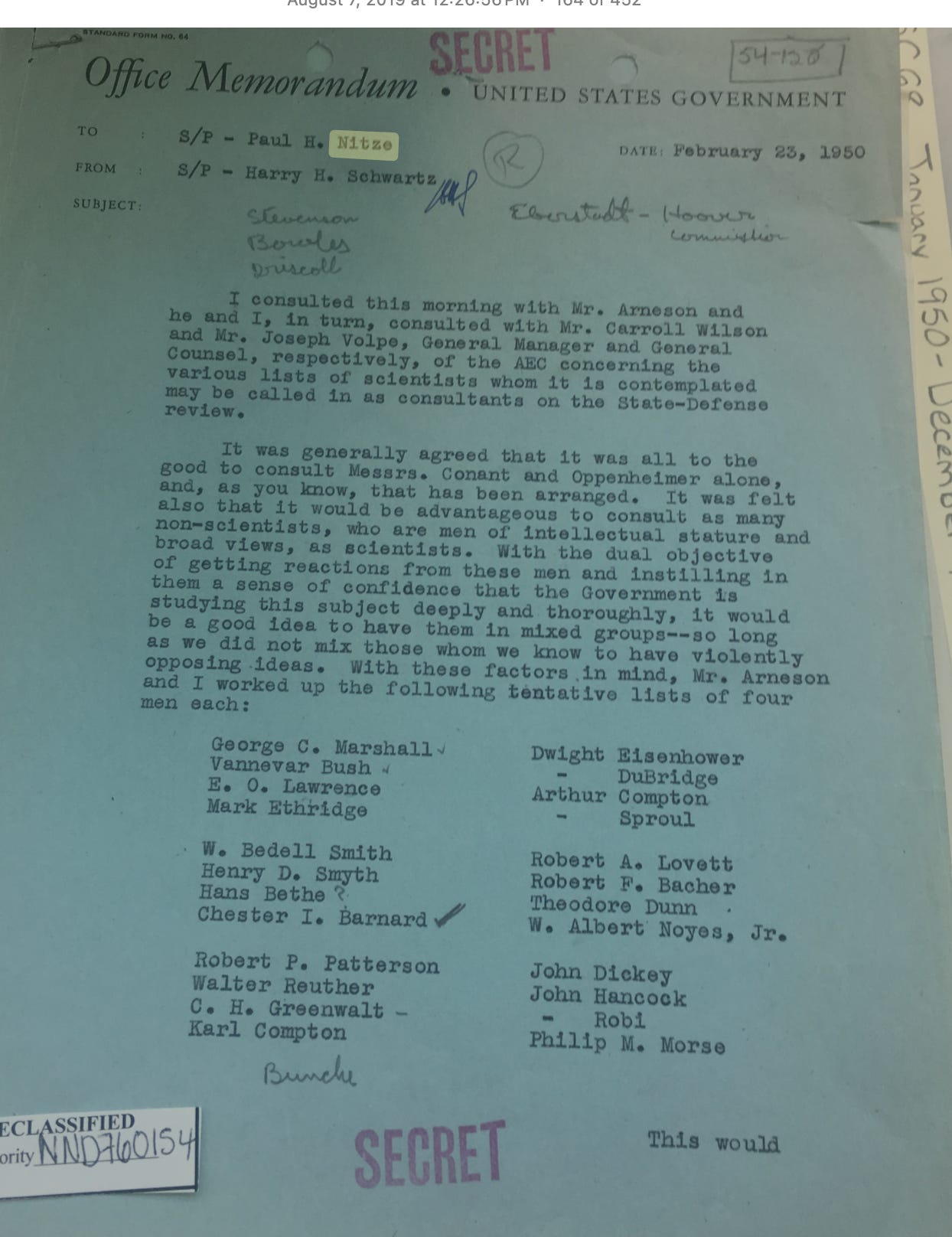

But the second glance has also turned up some interesting things I missed the first time. Here’s an example:

What are we looking at here? The primal scene in my dissertation/book is the preparation of NSC-68, an important planning document prepared in the State Department in the first months of 1950. NSC-68 is often called “America’s Cold War Blueprint,” but it’s not really a blueprint. It doesn’t contain a serious strategic concept, and its premises and rhetoric were vulnerable to withering critique, even in 1950, even within the State Department. The best internal critique, by William Schaub of the Budget Bureau, opens with the brutal subheading: “What, specifically, does the paper mean?”

The real meaning of NSC-68, as its sponsor Dean Acheson later stated, was “to bludgeon the mass mind of ‘top government’” into accepting a massive rearmament which would involve a permanent tripling of the defense budget. Up until mid-1950—despite Stalin’s varied misdeeds—not to mention the first Soviet atomic bomb test and the victory of the Chinese Revolution—Harry Truman was passionately committed to holding defense spending below a ceiling of $13.5 billion. Secretary of State Acheson, and his subordinate Paul Nitze (the principal organizer of NSC-68), believed the defense budget needed to be in the $40-50 billion range, though they excluded specific cost estimates from the document. They understood that putting the numbers in the document would instantly kill its political viability. Their strategy was military Keynesian in a precise sense: they wanted Truman to accept their qualitative definition of a pressing national problem, and then worry about how to “pay for it,” rather than starting from a definition of fiscal space available and tailoring defense spending to that constraint.

The authors of NSC-68 pursued a military Keynesian strategy: get Truman to accept their definition of a pressing problem, and then worry about how to “pay for it.”

There’s much more that could be said, but let’s get back to the archival image that inspired this post.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Origins of Our Time to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.