20 Errors in Gary Gerstle's "Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order"

Goldwater was chill about riots, Keynes liked deflation, and Biden's spending "almost reached World War II levels."

Gary Gerstle’s The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era was released last year by Oxford University Press and has met with nearly universal acclaim. I feel differently about the book, but there’s no accounting for taste. It is, however, important to note when a peer-reviewed academic book1 contains a significant number of errors, some of which I catalog below. There are other points in the book I hope to address soon—touching on what I consider to be more serious interpretive and evidentiary shortcomings—but in this initial post I have tried to limit myself to straightforward factual errors.

p. 36: “These fears form the critical backdrop to a massive foreign aid program for Europe, known as the Marshall Plan…Recipient governments had to meet a few requirements: They had to be democratic (rendering communist regimes ineligible).”

In fact, the offer was extended to communist countries, and Poland and Czechoslovakia showed some interest but were prevented from doing so by the Soviets (as expected by the American planners). Salazar’s Portugal, which was not a democracy, did receive Marshall aid.

p. 36: “Recipient governments had to meet a few requirements…they had to relinquish any desire to impose wrathful reparation terms on Germany”

This is not true either. At least into 1948, Britain and France participated on the basis of "assurances from the State Department that the results would not significantly alter their dismantling operations" in the German occupation zones (Hogan, The Marshall Plan, p. 175).

p. 37: “In October 1949, Mao Tse-tung’s communists emerged victorious in China’s civil war and immediately established a second communist state”

With apologies to Yugoslavia, Albania, Romania, Poland, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Bulgaria, Romania, Czechoslovakia, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, and Hungary.

p. 41: “what the sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld warned would be a ‘garrison state.’”

The sociologist in question is Harold Laswell.

p. 43: Eisenhower even endorsed the progressive, high taxation regime that the New Deal had put in place across the 1930s and early 1940s. Taft-style Republicans regarded the progressivity of that tax system as a horror, amounting to nothing less than a communistic strategy for confiscating and redistributing private property.

Taft was not opposed to the principle of progressive taxation. There is no footnote given to support Gerstle’s claim.

p. 49: Truman desegregated the Armed Forces in 1946

It was 1948. And actually what Truman did in 1948 was to issue an executive order stating “the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin,” to be “put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.” The Army didn’t even accept this in principle until 1950, and maintained segregated units for years afterwards. Segregated National Guard units persisted (with federal funding) into the mid-1960s.

p. 60: “Western companies such as Aramco, a joint British-American venture, had for decades done the drilling and refining of oil in, and shipping from, Saudi Arabia.”

Aramco, short for Arabian American Oil Company, was not a joint British-American venture. The company was a joint effort between four US companies: initially, Socal [Standard Oil of California] and The Texas Company, then joined by New Jersey Standard and Socony-Vacuum [New York Standard].

p. 95: “Goldwater’s nomination acceptance speech to the GOP… focused not on race but on restoring to America the creative, entrepreneurial spirit that Goldwater regarded as the nation’s birthright. In this speech, Goldwater targeted not civil rights protesters or rioters but the New Dealers, abetted by Republicans like Eisenhower.”

The claim that this particular Goldwater speech did not target civil rights protesters or rioters is false. To wit: “Tonight there is violence in our streets…Security from domestic violence, no less than from foreign aggression, is the most elementary and fundamental purpose of any government, and a government that cannot fulfill that purpose is one that cannot long command the loyalty of its citizens. History shows us - demonstrates that nothing - nothing prepares the way for tyranny more than the failure of public officials to keep the streets from bullies and marauders…We Republicans seek a government that attends to its inherent responsibilities of maintaining a stable monetary and fiscal climate, encouraging a free and a competitive economy and enforcing law and order.”

Incidentally, Goldwater gave this speech—in which, to repeat, he said “Tonight there is violence in our streets”—on July 16, 1964, the very day that a nationally significant riot broke out in Harlem, following the shooting of a black 15 year old named James Powell by Gilligan the Cop.

p. 95: “In this speech, Goldwater targeted not civil rights protesters or rioters but the New Dealers, abetted by Republicans like Eisenhower.”

The speech only mentions Eisenhower in order to praise him.

p. 122: “Reagan believed that…the American economy would flourish only when unions and a tax-rich government were brought to heel and, if possible, eliminated.”

In fact, Reagan did not believe the government should be eliminated.

p. 185: “New York City’s ascent as a center of global finance and cosmopolitanism occurred under the mayoralty of a law-and-order Republican, Rudolph Giuliani, who ran the city from 1994 to 2001.”

Where was the center of global finance in 1993, or for that matter the 1950s?

p. 262: “An all-white jury in Florida acquitted Zimmerman of wrongdoing in July 2013. ”

According to the New York Times, “all but one of the [six] jurors is white,” though none were black.

p. 272: “[Trump] would not allow American trade policy to be set by an organization in which the US was merely one voice among many. Each trade deal had to be a bilateral agreement with only two signatories.”

To view the full text of the agreement between the United States, Mexico and Canada, click here.

p. 275: “George W. Bush imagined a North American Union, similar to the European Union, that would have allowed the free movement of goods and people throughout the northern half of the Western Hemisphere.”

According to Snopes, there is no evidence of such a North American Union proposal. This doesn’t mean Snopes is right. What is Gerstle’s evidence? The single reference in the footnote is to Gerstle, “Minorities, Multiculturalism, and the Presidency of George W. Bush” (2010), no page number. That essay does not contain the phrase “North American Union,” but on pp. 265-266, Gerstle does indulge a bit of speculative fiction: “Bush and other Texans dreamed about making their state the pivot of what we might label a ‘Union of the Americas’ (UA), a trading bloc that would rival the European Union and East Asia in size, significance, and ease of trade” (emphasis added). What is the basis for this claim? Here again, there is one reference given at the end of the paragraph; it points us to John O'Sullivan, “Bush’s Latin Beat: A Vision, but a Faulty One,” National Review, July 23, 2001, 35–36. For those of you who read less Rod Dreher than I do, O’Sullivan is currently an agent of the Hungarian government, coordinating the pseudo-intellectual column of Orbán’s international brigades. This brings us full circle to the Snopes view that the North American Union is a right-wing conspiracy theory. I am less hostile to things labelled “conspiracy theories” than most other trained historians, but Gerstle would need to muster more evidence before he can support a claim as strange as this one.

p. 284: “Federal expenditures approved during the first year of [Biden’s] presidency constituted a greater percentage of GDP than those of the New Deal itself; they almost reached World War II levels.”

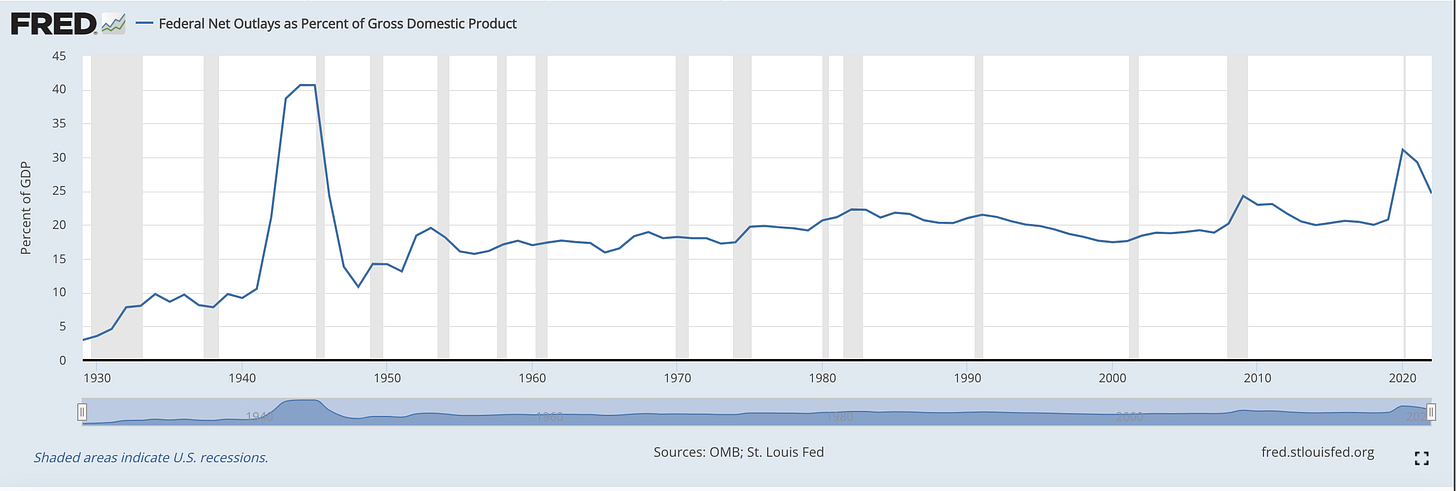

The first half of this is true, but trivial: federal spending as a percentage of GDP has been higher than it was in “the New Deal itself” in every single year since the New Deal. The second half of Gerstle’s sentence is false. The chart below (not given in the book) shows both things clearly.

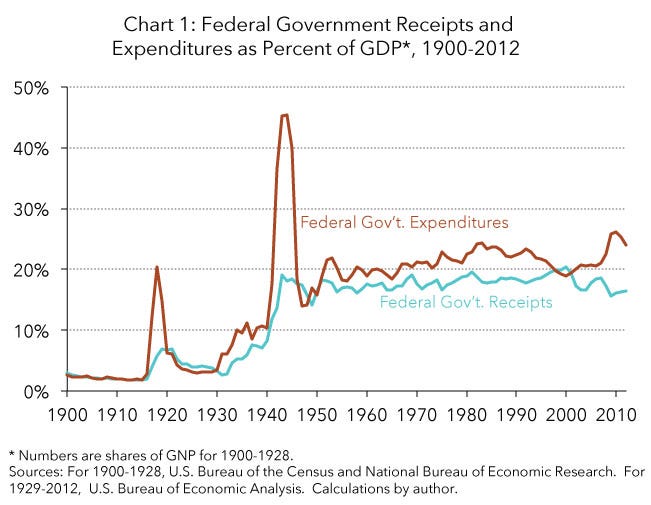

What is the source of the error? The footnote here cites two sources. One is from 2014, and contains the following chart:

Obviously, this chart cannot tell us anything about Bidenomics. But it does tell us two things of interest. First, that it makes no sense to hold out “the New Deal itself” as the standard for the ratio of federal expenditure to GDP. Second (and relatedly) the trend of this ratio shows that the shift from the New Deal order categorically cannot be described as a shift from “big government” to “small government,” despite Gerstle’s persistence in building his book around that image.

At least the second source Gerstle cites (from the St. Louis Fed) includes data from after 2012, which is crucial for evaluating Bidenomics. Here is the underlying graph:

If you compare this graph with the first one, you can tell right away that the two graphs are representing different things. That’s why the “New Deal” figure in graph #1 is never higher than around 10%, while the “New Deal” figure in Graph #2 is 40.1%. A little more examination reveals that the first graph shows annual federal spending as a percentage of annual GDP (that is, it shows the metric that Gerstle actually mentions in-text). This second graph shows something else. As the St. Louis Fed authors alert the reader:

Note that while total fiscal spending in both cases is spent over a number of years (i.e., the numerator), we use one year’s GDP in the denominator. For instance, the New Deal lasted roughly six years. While much of the recent federal spending will have taken place in 2020 and 2021, the latter two Biden plans (if passed) are likely to be spread out over about 10 years. It’s worth keeping that in mind when examining these numbers.

Having reconstructed the sources, we can see that Gerstle took the “43.2%” figure from graph #2 (which shows about 10 years of Bidenomics relative to a single year’s GDP) and compared it to the roughly 45% figure in graph #1 (where each data point shows a single year’s WWII spending relative to a single year’s GDP).

p. 310n70: “On Milton Friedman’s use of the term, see his ‘The Economy: We Are All Keynesians Now’…Nixon would himself run with this phrase in 1968 and beyond.”

Nixon did not say “We are all Keynesians now.” He said “I am now a Keynesian in economics” — and he said it in 1971.

p.315n26: “Keynesian doctrine taught that…when unemployment rose and fewer workers were being paid, consumers had less money in their pockets. They therefore spent less, rendering prices soft and vulnerable to decline, a decline that would, in turn stimulate new purchasing, more hiring, and then a return to an expanding economy.”

Keynes did not believe that unemployment and price deflation constituted a self-correcting mechanism through which recession would give way to expansion. This was precisely the view that Keynes devoted himself to destroying.

p. 317n44: “Volcker wanted to shrink the money supply.”

Volcker’s stated objective was to constrain the rate of growth of the money supply, not to shrink the money supply.

p. 317n44: “Volcker was not going to use the power of the Federal Reserve to pursue full employment. He did not regard job creation as part of the Fed’s mandate.”

The first sentence is true, though the refusal to pursue full employment just makes Volcker a typical US central banker (there is no discussion in the book of central banking during the “New Deal order”—no mention of the Fed-Treasury Accord of 1951; no mention of Marriner Eccles, William McChesney Martin, or Arthur Burns; no mention of the enormous efforts to defend the dollar against the “risks” posed by domestic expansion between 1958 and 1971). The second sentence in the quote above is false. Volcker’s concept, whether one buys it or not, was that high levels of unemployment were necessary to restore the conditions of a new economic expansion, in which (stimulated by appropriate monetary policy) new jobs would certainly be created though unemployment would not necessarily fall to the level previously considered adequate. Already in 1982, as he gingerly took his foot off the brakes, Volcker told Congress “The process appears to be starting, and the faster it takes hold the better the outlook for reduced unemployment.”

p. 317n45: “Carter also appeared indecisive in foreign affairs, especially in regard to the Islamic Republic of Iraq.”

This one is just a typo.

Gerstle, in his acknowledgments: “I would be remiss if I didn’t register my appreciation for the seven anonymous reviews I received via Oxford— four on the original book proposal and three on a near finished version of the entire manuscript.”

“Keynesian doctrine taught that…"

Wow, that one's really a doozy. Incredible.

The usual (and expected?) biases of an historian who writes on broad topics such as eras are to found in what they select to include or omit. The errors Gerstle makes are rather more egregious, reminiscent of those who begin with an ideology and write a narrative to support it.