Chile: Scenes from a Capital Strike

"The memos might have been written by a Marxist novelist depicting capitalist warmongers."

I. The Pepsi Challenge

Fifty years ago, the editors at The Economist cheered the violent destruction of Chilean democracy. Now, they are sick of talking about it. But the real conversation hasn’t even begun. How could it, when we still lack basic information? Just last month, we learned for the first time that Richard Nixon met personally with Chilean businessman Agustín Edwards on September 15, 1970. Edwards had flown to the US almost immediately after Chileans gave Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular a plurality at the polls on September 5. Edwards, who held the Pepsi franchise in Chile, wanted to see Pepsi executive Donald Kendall. Kendall knew the man who really mattered: he had been a close friend—and top donor—to Nixon since the 1950s. After Nixon’s failed bid for California governor in 1962, it was Kendall who got Nixon his job as a New York corporate lawyer; the future president’s $250,000 salary offset by the Pepsi business which suddenly materialized for the firm. Kendall’s NYT obituary contains a remarkable sentence: “The Nixon connection produced two foreign-policy coups.”

The NYT meant it metaphorically, like when Nixon steered Khruschev to the Pepsi booth in 1959. But there was at least one actual coup. On September 14, Kendall and Edwards met with CIA chief Richard Helms. According to Helms, Kendall then went to Nixon requesting “some help to keep Allende out of office.” On September 15, Edwards and Kendall met Kissinger and Attorney General John Mitchell for breakfast at 8:00. What we didn’t know until last month was that at 9:15 Edwards went to the Oval Office. Until his death in 2017, Edwards denied that he had met with Nixon. At 9:30 Kissinger came to the President's office.

Amazingly, there are still secrets being kept about these meetings. For example, who was the other person at the September 14 meeting with Helms, Kendall, and Edwards?

The CIA gets closer to telling the truth: three version of the same memo released over decades

It’s hard to think of a good reason. One possibility for the redaction is that the person is still alive. I don’t think this is a good reason, but it is certainly standard practice. A desire to protect the living might also explain why no declassification of documents was allowed to falsify Edwards’ denials that he had met with Nixon until Edwards was safely in the ground. And 1970 was recent enough that some of the players are still with us. People like Orlando Sáenz Rojas, head of the Chilean manufacturers association (SOFOFA). Back in 1974, NACLA identified Saenz as “one of the Edwards group's representatives who maintained a political relationship with the U.S. Embassy in Santiago…[he] spoke fluent English [and] established a very close relationship with Ambassador Davis,” who was his next door neighbor. “During the last month of the UP [Unidad Popular] Sáenz was also used as a go-between” between the Chilean Army and the U.S. Embassy. Also according to NACLA, Sáenz made several visits to the US during the Allende years, including three between January and July 1973.

As of August 2023, Orlando Sáenz Rojas was was still alive, and unrepentant: “Arrepentimiento del Golpe, no tengo ninguno.” Like Edwards, who persistently denied meeting with Nixon, Saenz downplays his direct contacts with the US:

How could I have contact with the CIA? Never. I met people from the Nixon administration when Allende had already fallen and I was in charge of the economic question. The only time that I saw Kissinger, after the coup, was in the General Assembly of the United Nations, October of 1973.

I have no reason to speculate if Saenz was the other man in the room on September 14, 1970. But I can imagine why the US government censors might not want to draw any attention to people like him while they’re still alive.

II. The Prose of Structural Power

Agustín Edwards’ September 1970 visit to the US produced one of the most famous lines in the history of American counter-insurgency: “Make the economy scream.” The sentence has stuck in people’s heads for a reason. It dramatizes into a single direct order (consisting of just four words) something that is usually invisible, deniable, impersonal. That “something” is the structural political power that accrues to people (or classes, or state agencies) whose decisions have consequences on a macroeconomic scale. Without firing a bullet or breaking a law, the decision to shut down a plant or cut off credit can cause suffering on a scale few criminals will ever match. When this threat is wielded effectively, it constitutes a significant qualification to the idea that democracies pick their policies by voting in elections.

The infamous sentence appears as an item in CIA Director Richard Helms’ notes on his meeting with Nixon on September 15, the same day Nixon had met with Edwards. Nixon gave Helms unambiguous orders to, in Helms’ words, “instigate a military coup in Chile, a heretofore democratic country.” As the spymaster recalled, “If I ever carried a marshal's baton in my knapsack out of the Oval Office, it was that day.” Things moved fast. According to one memo:

Late Tuesday night (September 15), Ambassador Edward Korry finally received a message from the State Department giving him the green light to move in the name of President Nixon. The message gave him maximum authority to do all possible—short of a Dominican Republic-type action—to keep Allende from taking power.

The source of this memo is as interesting as what it says. The memo was sent from employees of ITT’s in Santiago to ITT headquarters in New York. ITT was the 9th largest corporation in the US, and along with the copper companies, the most important US multinational in Chile. Even before Allende’s election, ITT had been a major intermediary between the US government and anti-Allende forces, largely because ITT director John McCone had until recently been the head of the CIA. The ITT memos, and a related set of cables by US Ambassador Edward Korry, contain a richer and more concrete version of the single bullet point: “make the economy scream.” To quote Anthony Sampson, whose 1973 book on ITT remains to my knowledge unsurpassed, the memos are “remarkable not only for the their revelations about plots” but for their tone. “The language was brutal and callous; the memos might have been written by a Marxist novelist depicting capitalist warmongers.”1

The memos constitute the written residue of an anti-Allende network that involved American business (like ITT), internationally-connected members of the Chilean elite (like Agustín Edwards), and the Santiago branches of the US state (particularly the CIA and the American Embassy). In between Allende’s election and Edwards’ trip to the White House, Edwards (described by journalist Thomas Powers as “a longtime ally of the CIA”) met with the CIA station chief as well as Ambassador Edward Korry. On September 13, ITT’s Hal Hendrix attended a meeting at the home of Arturo Matte, a wealthy Chilean industrialist. There, the plotters sought to square the circle between constitution and coup by imagining that

a constitutional way out...doesn't preclude violence--spontaneous or provoked. A constitutional solution, for instance, could result from massive internal disorders, strikes, urban and rural warfare. This would morally justify an armed forces intervention for an indefinite period.

From this framework emerged increasingly detailed plans for “economic chaos.” On September 14, Ambassador Korry wrote to Kissinger:

Terror is the key weapon now being employed by the Allende forces. But there is a counter-terror weapon—the economy…[outgoing President] Frei must be prepared to…frighten the hell out of his Armed Forces and to panic the country into more dire economic circumstances.

Part of the plan for economic chaos was to talk about economic chaos. As Nixon once said in a different context, the economy is what people think it is. On September 22, Korry wrote:

The action that would spark the shuffling of military into the government deck would be a report to the nation this week by the Minister of Finance, Andres Zaldivar. He and his close associate Minister of Economy Carlos Figueroa, have ostensibly been preparing the past few days a “technical” report on the state of the economy for the President. They have been aided by teams of specialists on each sector of the economy. All participating in this “study” are bound by only one glue—their total opposition to Allende…Both these gentlemen [Zaldivar and Figueroa] are ready to resign if Frei gives the green light; the military is ready to assume portfolios that would flow from the collective resignation of the entire cabinet…The service chiefs in considering this possibility have stated they wished to keep Ossa as Min Defense and Zaldivar and Figueroa as “technicians” in fields in which they confess their total ignorance.

On September 23, Zaldivar gave the speech predicting economic disaster. Ambassador Korry approved: “Zaldivar economic report to nation last night excellently prepared and designed to worsen bad situation.” He encouraged Washington to “give widest distribution to U.S. press and more importantly business and banking community.” Korry and someone who had worked on the speech talked about next steps. The name of interlocutor—presumably a Chilean with extensive connections to business and the Chilean Christian Democratic Party [PDC]—remains classified:

[less than 1 line not declassified] told me last night after leaving late afternoon lengthy cabinet meeting that had edited Zaldivar’s report that those such as himself who wished to stop Allende were not getting leadership from Frei… [less than 1 line not declassified] the one factor that could change the entire situation would be a faster downturn in the economy. If that could be provoked, it would affect military outlook and even PDC’s, particularly if such downturn occurred before the PDC junta and reached maximum velocity before October 24th.

In this cable and one the next day (September 25), Korry relays a catalog of specific means. There are statements along the lines of: “The economic situation is bad and it would be good if it got worse”; “The economy will tend to turn up if a conscientious effort is not made to have it go down. People will start to buy in normal terms once they believe Allende is definitely the president”; “[name not declassified] will cooperate in blocking an upturn if there is any possibility to do so legitimately and in some cases, illegitimately.” And so on.

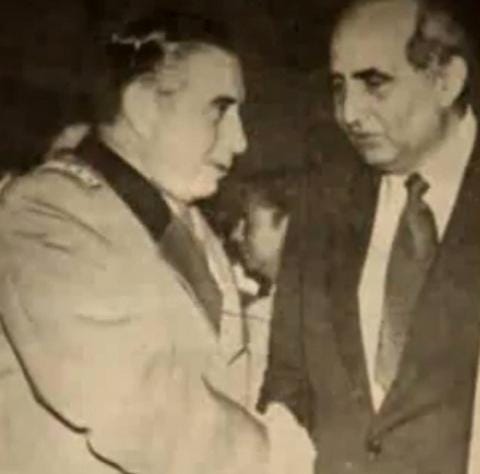

(Above: Augusto Pinochet and Agustín Edwards, via National Security Archive)

Korry embeds all this an astute political theory of the challenges facing any new government of the democratic left:

Popular Unity will come to power as an inherently unstable coalition, afflicted from the outset by ideological differences, political opportunism and corruption, incompetence and inevitable administration confusion…Its decision-making machinery…is likely to function in the creakiest of fashions; its economic and managerial expertise in key positions is likely to be mediocre or worse. These problems can be overcome as Allende and his Communist partners gradually gain control. But meantime Allende’s GOC will face the critical problems of making a fairly complex economy and government work, while delivering on promises of revolution and a better life for all.

According to Korry:

“It will be during this period—perhaps six to nine months—that Allende’s Popular Unity will be most vulnerable. If the economic and administrative problems are sufficiently severe, Popular Unity could crumble. This is the scenario that would unite the army and set the scene for effective, popularly-backed military intervention. The PDC [Christian Democratic Party] is preparing for that day—at least some of the healthier elements by worsening the economic situation [less than 1 line not declassified].”

Korry proposed that the US get in on the act:

If one large enterprise here were to shut its doors next week, if one bank were to fail, if one savings and loan association were to collapse, we would still have life before October 24th and we would be contributing to the chaos that has its natural yeast in any case. I see no risks in pursuing with U.S. companies in the U.S., particularly if one totally discreet leader were selected (may I suggest the name of [name not declassified], the suggestions put forward by [name not declassified].

Korry proceeds to list “Some objectives we could support without repeat without showing the USG hand are the following,” including:

Let the business community know about the unlikelihood of any exit for technicians and managers and professionals after November 4th. … The fewer the brains, the more difficult the management problem for Allende; Stop bank credit and as much other credit as possible … Consider having one large U.S. company fold up. Ford has a perfect justification for doing so and it is doomed. General Motors should not try to hang on …. The Bank of America is almost bankrupt here; why should it hang on? … It is natural for the GOC’s 51 per cent management (all PDC) to cede to their wishes and give a whopping big raise that would have all other workers in the country clamoring for one.

One thing that fascinates me about these cables is that you can read them as an inversion of the “political business cycle” that can arise through the interaction of macroeconomic management and electoral politics. The most famous practitioner of this, of course, was the same man who took out Allende. Nixon told Helms to “make the [Chilean] economy scream” on September 15, 1970. On November 3, 1970, in the midst of a recession, the US held midterm elections, which went badly for the GOP. On November 11, Nixon told John Ehrlichman that “the economy must boom.” A veteran of the CIA’s campaigns in Chile once remarked, “You buy votes in Boston, you buy votes in Santiago.” You make the economy boom in Southern California, you make the economy scream in the Southern Cone: the abstraction is versatile.

Another mirror-image here is the importance of psychology and systemic interdependence, which reads like a funhouse mirror version of the crisis-fighting bailouts which were being pioneered around 1970 in other precincts of the US government. Korry proposes “to make the consumer more doubtful about the economy and less willing to spend.” He considers the prospects for a financial crisis:

If one large enterprise here were to shut its doors next week, if one bank were to fail, if one savings and loan association were to collapse, we would still have life before October 24th…Mention specifics in any propaganda that the business community (again I caution not the USG) can spread. The two savings and loan associations I mentioned in Part I (Calicanto and Casa Chilena) and the Banco Hypotecario (an Alessandrista group that is the No. 1 target of both PDC and U.P.) are on the ropes and only need a very slight shove.

An ITT memo from September 29 entertained similar hopes:

Undercover efforts are being made to bring about the bankruptcy of one or two of the major savings and loans associations. This is expected to trigger a run on banks and the closure of some factories, resulting in more unemployment. The pressures resulting from economic chaos could force a major segment of the Christian Democratic party to reconsider their stand in relation to Allende in the Congressional run-off vote. It would become apparent, for instance, that there is no confidence among the business community in Allende's future policies and that the over-all health of the nation is at stake. More important, massive unemployment and unrest might produce enough violence to force the military to move.

During an internal review of potentially damaging items that might be raised by the Church Committee, US intelligence officers noted:

The other potential embarrassment centered on the report that Chase Manhattan Bank had cancelled a line of credit to Chile, an act which presumptively was at CIA insistence. Chase Manhattan had indicated to the Committee that it did not want to discuss the reasons for the cancellation, so it was natural to conclude that CIA had been behind it.

Just as the political business cycle was being undertaken in different ways in different hemispheres, the increasing awareness of financial interdependence was also showing up in a domestic US context at exactly the same time as the mobilization against Allende. During the summer of 1970, concerns about the stock market, corporate liquidity, and the unregulated money markets led Fed Chair Arthur Burns to reassure business leaders that he stood ready to do whatever it took to head off a “crisis of confidence.” Government initiatives to relieve pressure on private institutions, like Chrysler, were justified as the containment of systemic risk. The bankruptcy of a railroad was said to risk “possibly collapsing the economy on domino theory.”

In a well handled financial crisis, the mere announcement of a backstop could be enough to relieve difficulties, an ideal solution in which the government could accurately claim it had done nothing that merited the label “bailout.” In Chile, everything was reversed: the ideal solution would be one in which persistent whispers about economic chaos proved to be self-fulfilling, so that one could stand back and point to their clean hands. Who could question that corporations and banks had the right to make decisions that could cause unemployment? Foreign direct investment was a privilege, not a right. And if “massive unemployment and unrest might produce enough violence to force the military to move,” who could blame the military?

Anthony Sampson, The Sovereign State of ITT (New York: Stein & Day, 1973) 260.