A few weeks ago, I did a two-part interview on Dan Denvir’s The Dig, which in my somewhat biased opinion is the best podcast out there.1 Of all the views I expressed, the most controversial within the left might be my thoughts on asset price inflation. There are a couple aspects to discuss there, and this post sets out in more detail my thinking about one aspect: the common claim that that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy since 2008 has increased inequality, specifically wealth inequality.2

The basic idea is that sustained low interest rates and quantitative easing lead to an increase in asset prices, and thus (since asset ownership is distributed extremely unequally) to an upward redistribution of wealth. The complaint can be heard left, right, and center, from Jacobin to the Koch-funded Mercatus Institute to the Financial Times. It comes from people with only a casual knowledge of the Fed as well as from brilliant scholars who know more about money and banking than I ever will. Yet, as we will see, the evidence for the claim is extremely thin, bordering on nonexistent.

The uses of perversity

The idea appeals to certain intuitions including, for those of us on the left, the suspicion that macroeconomic policy under capitalism is always a choice between bad options. On the center and right, by contrast, there may be a more perverse appeal: the idea can confuse and disorient their political enemies by implanting the sense that progressive dovishness is at odds with progressive egalitarianism.3 Meanwhile, talking about inequality while arguing for punitive Fed policy offers these avowed anti-egalitarians a zero cost opportunity to pretend like they have a social conscience. Less cynically, the idea that the benefits of low rates (higher employment) are perfectly balanced by downsides (more inequality) perfectly matches the both-sides-ism so common in our media and chattering classes.

A perfect example of this algorithmic compulsion for “balance” appears in Wall Street Journal reporter Nick Timirao's recent(ish) book on the Powell Fed. As reportage, I can recommend the book highly, and despite a few quibbles I even enjoyed the brief historical sections. But the book’s few, cautious ventures into normative evaluation read like a compendium of received ideas, presented with a certain indifference towards the merits. Thus, Timiraos claims that the central bank faces an impossible dilemma on social justice. On the one hand, “low-rate policies have…contributed to—a longer-running widening of wealth inequality.” But if “the Fed raises rates to prevent inequality,” this will come “at the expense of growth and hiring.” Such an attempt to foster equality will lead to its opposite: “whereas growing wealth inequality can corrode politics, so too can high joblessness and income inequality.”4

But the evidence Timiraos presents for the supposed impasse is not just weak but outright contradictory:

The Fed’s low-rate policies have coincided with—and contributed to—a longer-running widening of wealth inequality. Trillions of dollars in triage can save the financial system, but the Fed’s economic-stabilization tools are blunt. In 2008, household wealth fell by $8 trillion. It rose by $13.5 trillion in 2020, spotlighting the unequal distribution of wealth-building assets such as houses and stocks. The wealthiest 1 percent of US households were $5 trillion richer at the end of 2020—a nearly 15 percent gain in their net worth. The bottom 50 percent, by contrast, saw their net worth rise just $367 billion—a better percentage gain (18 percent) but still a scandalous wealth disparity.5

Nothing here supports the claim that “The Fed’s low-rate policies have contributed to—a longer-running widening of wealth inequality.” In fact, the evidence presented points in the opposite direction: the bottom 50% saw their net worth increase more in 2020 than the top 1% did, implying a (very, very small) reduction in inequality.

Consider again the sentences:

The Fed’s low-rate policies have coincided with—and contributed to—a longer-running widening of wealth inequality … In 2008, household wealth fell by $8 trillion. It rose by $13.5 trillion in 2020, spotlighting the unequal distribution of wealth-building assets such as houses and stocks.

This seems to imply is that the collapse in wealth in 2008 was egalitarian, while the increase in 2020 was the opposite. But the 2008 crash and resultant recession was disastrous for the bottom 50%, who saw their share of net worth decline by 1.8 points and their absolute wealth decline by $1.19 trillion, or 82%. By contrast, following 2020 the bottom 50% saw increases in both relative and absolute terms. The implied contrast between—2008 vs 2020—only reinforces the weakness of the supposed tradeoff between avoiding recessions and increasing wealth inequality.

No egalitarian could disagree that the resulting level of inequality is still scandalous. But one might wonder why a reporter for the Wall Street Journal—a world-class newspaper and invaluable source of business news, but hardly a frequent advocate of economic equality—discovers inequality at the very moment he is groping for reasons to worry about low interest rates. In context, the fallacy is not the prelude to a call for more egalitarian Fed policy. Timiraos explicitly argues that the American people should not demand that the Fed do anything “to correct politicians’ mistakes or broader social ills.” It would be bad if “the public demands unelected technocrats solve problems their tools can’t readily address.” For example, “the Fed lacks the tools to deal simultaneously with unemployment and inequality.” The practical implication of an ostensible concern about inequality turns out to be: do nothing.

The politics of convergence

Just because as a Wall Street Journal reporter says something, doesn’t mean leftists should not. In fact, the world would be a better place if leftists could absorb all of the true and interesting things that the business press says on a daily basis. But it is striking that the ideological convergence has been ignored or even disowned. For example, Doug Henwood (whose Wall Street is outstanding in the too-small field of Marxist business studies) wrote that asset price inflation “is something the bourgeois media doesn’t talk about as much as the regular consumer kind.” But this isn’t a very good description of the bourgeois press, much less the fact that the very idea of asset price inflation was invented by central bankers and first gained ground on the right.

In the same piece, Henwood writes that the former FOMC member Thomas Hoenig (who Henwood admires for his extreme hawkishness) isn’t “a conventional inflation hawk, one of those cranks reading Friedrich Hayek and worrying that the wrong sorts of people (workers) might be making some money.” But Hoenig has repeatedly described himself as “an Austrian economist” or someone “influenced by the Austrian school of Ludwig Von Mises and Friedrich Hayek.” Regarding workers, Hoenig wanted to hike rates in October 2009, with unemployment hitting 10%, and complained the next year that sales in his district were being held back by “people who are on unemployment [and who] will not come off it for those more modest wages.” The “crank” part may be subjective, but Hoenig is the kind of person who responds to an interviewer’s stray reference to wheelbarrow prices by instantly launching into a Pavlovian monologue on Weimar wheelbarrows full of money.

Reality intrudes

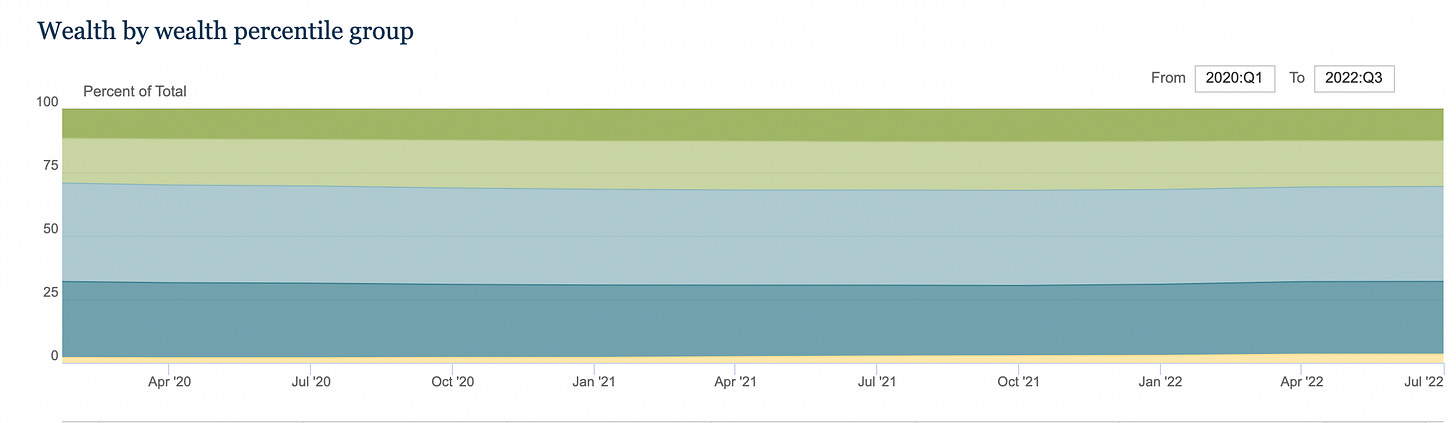

I think it’s important for Marxists to avoid becoming unwitting vehicles for right-wing ideas, but clearly the most important reason leftists should think again about this talking point is just that it doesn’t seem to be true. The Fed’s Coronavirus interventions have been described by leading Marxist scholars as a “politically driven upward redistribution of wealth” without precedent in the history of capitalism. But as the chart below shows, it is hard to see the “escalating plunder” in the distribution of net worth by percentile groups:

Zooming out, the record still provides little evidence that ZIRP and QE contributed causally to the widening of wealth inequality. It’s not even clear that they coincided with any significant widening of wealth inequality.

Between 2007 to 2022:

-the top tenth of the top 1% increased their share by 0.6%

-the the rest of top 1% increased their share by 1.1%

-the 90th through 99% percentile decreased their share by 0.4%

-the 50th through 90th percentiles decreased their share by 2.7%

-the bottom 50% increased their share by 1.3%

To the extent that any shuffling occurred, the upper-middle group (50-90th percentile) lost ground, with their relative loss balanced out by the relative gains at the top and the bottom. The big picture, it should not surprise us, is persistent inequality. Over the course of the 15 year span, the bottom half of the country owned basically nothing, with their share of total net worth—held largely in housing—falling as low 0.4% in 2011 and rising as “high” as 3.3% in 2022. Throughout the entire period, the top 1% of households held over one quarter of all net worth, and the top 10% around two thirds.

Taking a step back: where do asset values come from?

To the extent that the top 10% did increase their share of total wealth in the low interest rate era, it is not clear how much of this increase should be attributed to low interest rates. Rising asset prices reflect a number of different factors. Take housing, which represents not just the major store of wealth for people who own wealth but also a major share of total wealth. This class of asset prices is clearly influenced by supply constraints. These range from the NIMBY land use stuff you hear most about, to some more fundamental facts about capitalism: the industry is extremely cyclical, so that the 2008 crash led to a contraction in production from which we have still not recovered; more than that, at no point in the business cycle will profit-seeking builders find it profitable to build for a large share of the population whose incomes are too low.

Even if it’s true that higher interest rates, by tightening mortgage finance, might lead housing prices to fall to some extent, it should be obvious that that this would not not only make mortgage payments for working and middle class people more expensive, but also fail to come anywhere close to touching the fundamental sources of the housing shortage. Both reality and politics suggest that people on the left should not focus on easy money as the culprit here.

What about stocks and bonds? Clearly, financial markets are sites of speculation, and the availability of liquidity can play a role in speculation.6 But, as Nathan Tankus has put it, the stock market is less disconnected from the 'real economy' than you may think. To the extent that stock prices reflect earnings expectations, the “inflation” in this type of asset prices reflects distinctly nonmonetary sources of inequality. This is expressed clearly by the late economist Lance Taylor, in a book which happens to have “asset price inflation” in the subtitle. Despite this, Taylor (and his co-author Özlem Ömer) do not see the phenomenon in terms of artificially “pumped up” asset prices:

Higher capital gains were stimulated by wage repression in two ways. Businesses enjoyed rising profits and falling interest rates, the latter due to slower inflation because there was no wage-driven cost push. Insofar as asset price increases are driven by capitalization of higher profit rates as interest rates declined, they basically result from lagging wages.

In this picture, asset price increases reflect something “real” (the distribution of income between wages and profits. What’s more, while low interest rates play a role in the explanation, the low interest rates are themselves presented as the result of the same “real” development, that is the destruction of labor’s capacity to impact the price level.

In short, it is a mistake for leftists to locate the source of inequality in monetary policy per se. Writing this, I was reminded of a passage by the historian Jeffrey Sklansky from his excellent history of earlier American monetary politics:

the social relations that determined who made money depended in turn on a broader struggle over labor and land as well as currency and credit. The power of small farmers and traders in colonial New England came from their control of farms and shops no less than of bills of credit and public loan offices. So too, the ascendance of corporate capital two hundred years later entailed a sweeping reconstruction of property in the means of production, transportation, and communication along with the means of payment. The organization of money is hardly the lone or essential basis of economic exploitation, nor is financial reform a panacea for systemic conflict and crisis. We would do well to remember what early Americans recognized, that the money question was always about more than money.

The Fed is an engine of inequality—when it tightens

If you’ve made it this far in the post, you probably know that more dovish monetary policy is better for workers because it leads to tighter labor markets, higher wage growth, and more worker bargaining power. There’s no need to go on at length about this but it is worth restating here: contra Timiraos, the Fed is not bereft of tools for addressing inequality. Far more people live on labor market income than on their wealth, and the Fed’s policy works largely through the channel of the labor market. Leftists who describe 2020-2022 as an era of skyrocketing inequality driven by the Fed mistake not only the real causes of inequality but also the real distributional effects of the labor market on inequality in these years, which is obvious from the headlines but is also quickly being documented in important studies). Anyone who says that dovish policy trade off higher employment against intensified inequality, without discussing income inequality or the labor market, is either misinformed or willfully dishonest.

Rational kernels

Usually when people are upset about something there’s a good reason. In this case, I think that the idea that the Fed’s easy money has driven inequality reflects valid—indeed, urgent—concerns. For one thing, even if the claim that easy money has widened inequality is false, it is true that these policies have contributed to the reproduction of what even the Fed’s research staff realizes is “a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.” If your counterfactual comparison is not easy money versus hard money (that is, Thomas Hoenig’s desired alternative), but rather post-2008 stabilization policy against a new New Deal, then it is easy to understand that the response to the 2008 crisis has fallen short of other, easily imaginable responses to crisis which would reduce inequality rather than sustaining an existing, scandalous level of inequality.

Another rational kernel in the asset price confusion is that it really is true that the Fed works hand in glove with the private financial sector. There are countless obvious signs of interest-group capture, though they don’t come close to providing any understanding of the specific mediations through which the Fed’s relative autonomy ends up reinforcing the power of finance as a class. Even if you leave interest to one side, it’s enough to know that, as Janet Yellen said, “we work through financial markets.” Her predecessor Alan Greenspan once put things more dramatically when he said nothing should “induce us to do things that will undercut the system that we are beholden to serve.” People accurately see that the Fed is (in some complicated way) beholden to serve an unjust system; they see the stock market going up; and they reasonably look for a connection.

The question, then, is whether dovish or hawkish policy creates a better terrain for attacking the real sources of inequality, and for developing a critical public discussion about the divergences between the Fed’s alliance with finance and the good of society as a whole. I’ve not yet seen a good argument that there is anything to be gained from the tactical alliance with the hawks. People on the left should tend to view handwringing about easy money and inequality as, at best, a misunderstanding and, at worst, a feint by the enemies of equality.

The latest episodes, featuring one of my favorite scholars, Michael Denning, on one of my favorite thinkers, Antonio Gramsci, are excellent and may be especially interesting to anyone who finds this themselves reading this newsletter.

My thinking on this subject is most indebted to Nathan Tankus, whose response to Rana Faroohar’s centrist version of this trope is well worth your time.

I use the word “perverse” to recall Albert Hirschman's classic The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy. The perversity argument, writes Hirschman, is the claim that “the attempt to push society in a certain direction will result in its moving all right, but in the opposite direction. Simple, intriguing, and devastating (if true), the argument has proven popular with generations of ‘reactionaries’ as well as fairly effective with the public at large.”

Emphases in original.

Emphases added.

Though, as the late 1920s and 1980s suggest, high interest rates are not obviously a barrier to speculation. I hope to write about more about the 1920s as a prehistory of “asset price inflation” in a future post.

Finally got around to this. Great piece. Reminded me of a recent paper by Goldstein and Tian which shows there has actually been a decline in the number of financial rentier households during this period across most countries. One of the biggest reasons they find is lower interest rates (not usually accounted for in the kind of QE = wealth inequality narratives you critique). I've also shown lower rates have sharply reduced non-financial sector "financialization." To the extent this kind of financialization exists (I think it's a very exaggerated phenomenon despite some orthodoxy) and is said to be driving inequality, it's telling most of those effects were pre-crisis / pre-QE.

LInk to the Goldstein and Tian paper:

https://academic.oup.com/ser/article/20/4/1567/5940652

Yeah, that:

https://twitter.com/AnthPB/status/1560649203767992321?t=xEf49XrSdt9vf4xJaKVxfw&s=19