Noah Smith Watch: Double Counting Fracking Jobs

Lobbyists heard the good news about multiplier effects a long time ago

In the course of arguing that Kamala Harris “needs to be Pennsylvania fracking's biggest champion,” Noah Smith writes:

Usually, both politicians and pundits think about the economic importance of something like the Marcellus Shale in terms of how many jobs it directly supports. No one knows exactly what this number is for the state of Pennsylvania, but industry estimates are around 123,000. A lot of people, especially climate activist types, will dispute that figure and claim that it’s an overestimate. But in fact, it’s probably a big underestimate, because of economic effects that even the fracking industry itself doesn’t understand. I’m talking about local multipliers.1

Smith then goes on to helpfully explain multiplier effects. Some portion of fracking revenue gets spent locally, which supports jobs in various consumer sectors: restaurants, barbers, etc. Smith claims:

Those jobs almost certainly aren’t included in the industry association’s estimates — if you said that jobs in pizza restaurants and hair salons were supported by fracking, the climate activists would laugh at you.

When I read this, I thought it was weird that the industry’s own estimate would ignore indirect employment of various kinds. I’ve read plenty of similar lobbying material related to the defense sector, and at least since the 1960s, these have typically been equipped (or, depending on your persuasion, padded) with casual and not-so-casual multiplier analysis.

So I clicked through to the ultimate source of Smith’s 123,000 “direct” jobs estimate, which happens to be a report by FTI Consultants called Economic and Fiscal Impact of Pennsylvania Shale Gas Development. There, I found exactly what I expected. Smith is just plain wrong in his claim that the “123,000 jobs” estimate refers only to direct employment effects. On page 1 of the report, we read:

These jobs include those directly supported by the industry and those generated through the supply chain and employee spending across different sectors of the economy.

The industry report goes on to describe “these ‘ancillary’ or ‘ripple’ effects” in quite a bit of detail:

Direct Effect – direct employment or expenditures associated with maintaining the industry. Examples include construction or environmental workers.

Indirect Effect – the direct employment or expenditures effect on the regional supply chain. For instance, equipment and material inputs used in constructing new warehouses. The supply chain can also include services such as architecture, legal, and engineering services.

Induced Effect – consumer spending by direct and indirect employees. Examples include the spending by direct employees or the employees of the businesses within the supply chain. These workers take their paychecks home and eventually spend them on their daily needs. This supports the other sectors of the economy, such as real estate, healthcare, education, retail, transportation, and entertainment.

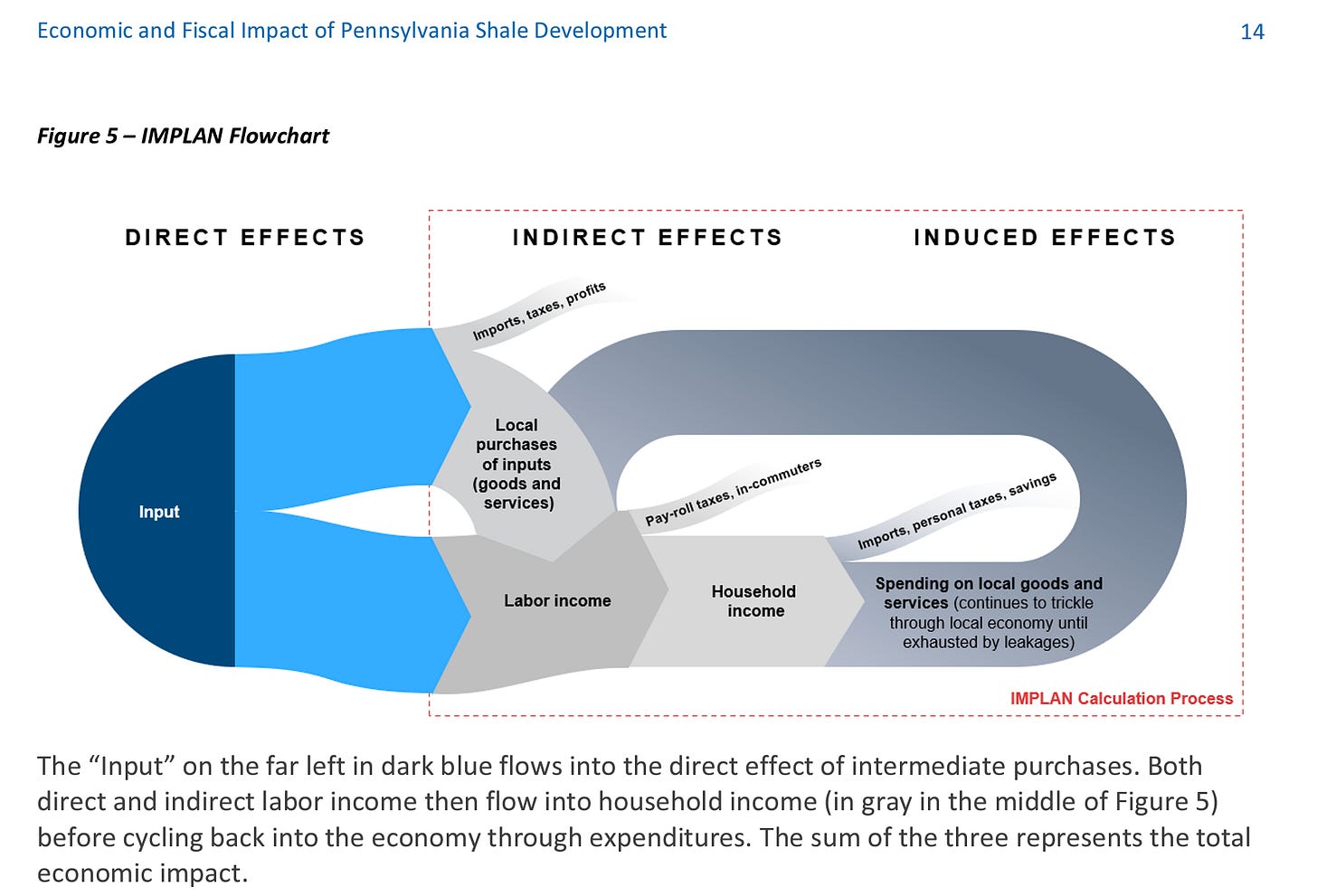

Total Effect – The total effect is the sum of the direct, indirect, and induced effects. Figure 5 shows a representation of these effects in IMPLAN as a flowchart.

So when Smith claims that 123,000 is “probably a big underestimate,” he’s not just making a completely unsubstantiated empirical claim. He’s conceptually engaged in a kind of misleading double counting. The number already includes ripple effects.

What’s the lesson here, besides that Smith doesn’t read the things he links to? It’s that Smith’s intuition about lobbyists-as-economists is totally wrong. They’re not the naifs he supposes they are. They—or, rather, the consultants they hired to produce these estimates—are often more technical than Smith. The fracking lobbyists he cites, for example, dive explicitly into such matters as Wassily Leontief’s input-output analysis and its descendants, such as the “IMPLAN Model.”

Nor do lobbyists expect to be laughed at if they say “that jobs in pizza restaurants and hair salons were supported by fracking.” As a matter of fact, lobbyists have been using analysis like this since the Cold War. Here is one example, from 1963, which I picked more or less at random:

More important, possibly, is the function of defense economic activity within the system of the Colorado economy. Defense economic activity results in the import of purchasing power into Colorado, in exchange for the export of defense goods and defense services. Thus, defense activity can be described as a basic industry, which buys goods and services locally and thus supports more economic activity in local service industries. Both this direct and indirect defense economic activity induce demand for consumer goods and services which then is manifested in further support of the local service industries. The sum of all these makes up the gross economic impact that defense spending brings to the Colorado regional economy.

How great is this total economic impact? Just how much of the Colorado economy depends on direct defense activity, indirect defense activity, and defense-induced consumer demand?

We have no precise answer. No study has yet been made of the interindustry relationships in the State of Colorado. However, such studies have been made of other regional economies, and their results give us a basis for estimating the order of magnitude of the gross economic impact of defense spending in Colorado. The crucial information in these other studies is the multiplier factor indicating the additional jobs in the study area supported by each direct defense job, or the sage from a factor of $0.85 additional personal income from military aircraft production in the St. Louis metropolitan area (a 1958 study by Werner Hirsch); to a factor of 4.03 additional jobs eventually supported by each defense manufacturing or construction job in the state of California (a 1960 study by Tiebout, Hansen, and Robson).

The Colorado economy probably lies between those two extremes…

This is a major form of vernacular Keynesianism, and one which has had meaningful effects on our political economy. Viewing it as some kind of arcana—“economic effects that even the X industry itself doesn’t understand”—is an idea so bad it had to come from an economist.

In bold is my emphasis; initalics are Smith’s emphases.