The Geometry of Mass Graves

If your dad owned his own private Rothko chapel, would you commit a genocide?

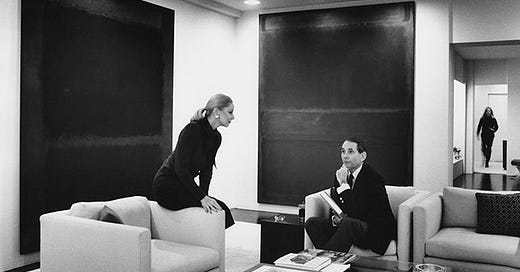

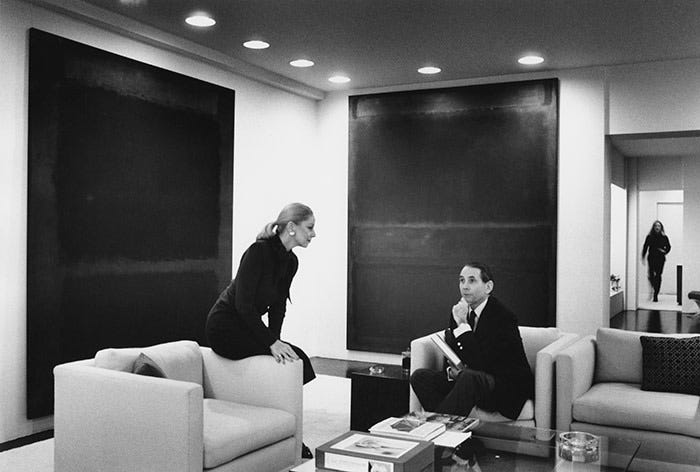

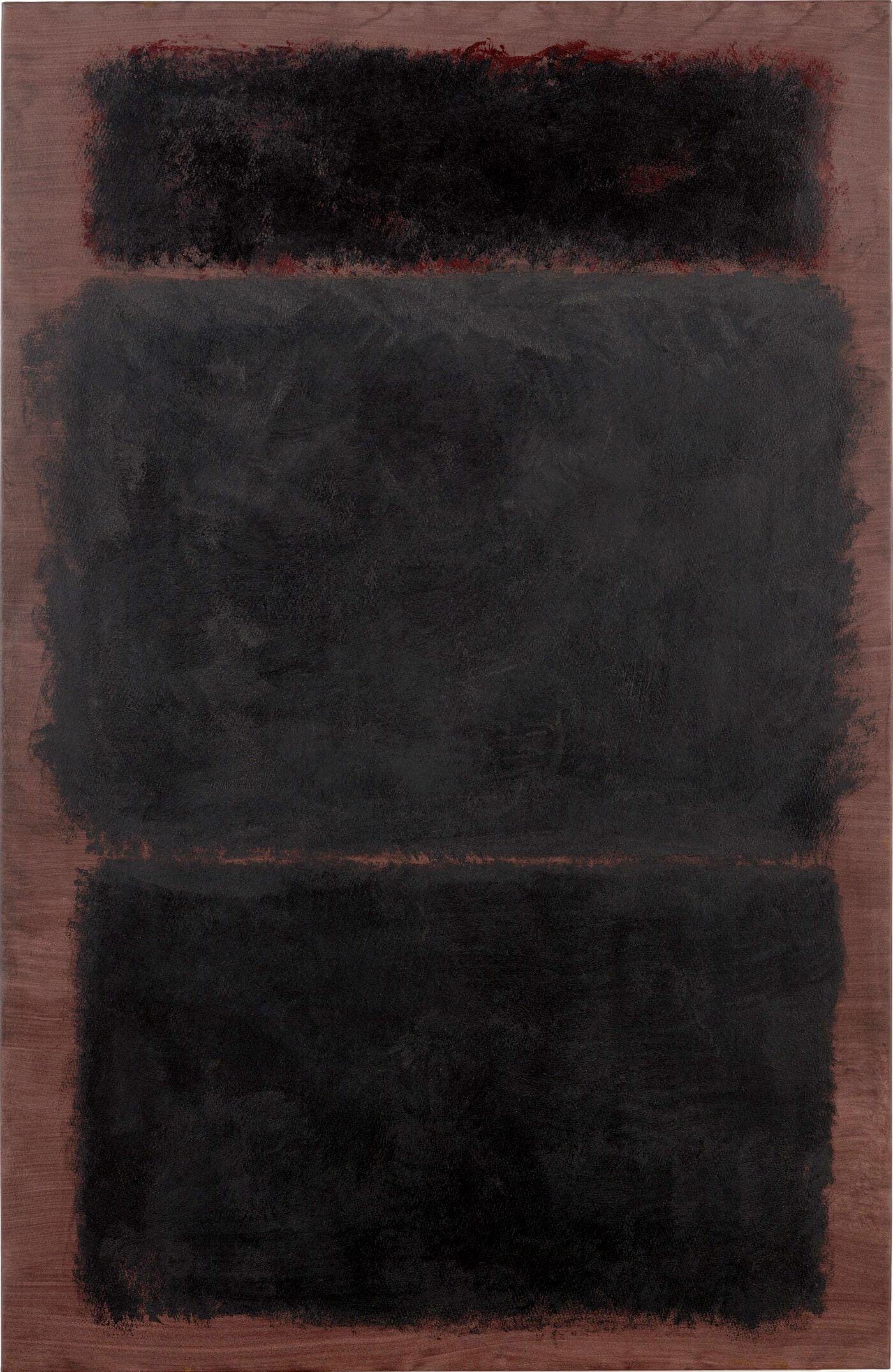

Most people have to go to a museum to seek out a spiritual encounter with Mark Rothko. But Antony Blinken grew up surrounded by the gauzy masterpieces. His father, Warburg-Pincus cofounder Donald Blinken, bought five canvases directly from the artist, whom he considered a friend. Rothko himself hung the paintings. Besides money, the relationship was built on shared experience. Rothko, like Donald Blinken’s father, was born in the Russian empire around the time of the Kishinev pogroms. Rothko told people he had “always been haunted” by an image from a story told to him when he was a child: local Jews driven into the woods by Cossacks and forced to dig themselves a square grave.

Did young Antony Blinken ever hear a version of this story? Did the color fields on the wall at home ever remind him of mass graves? We know that he grew up thinking about the death camps, largely through the prism of his stepfather Samuel Pisar’s experience in Majdanek and Auschwitz. As a college student, Tony Blinken described watching Salvadoran death squads on the evening news:

As the reality of the death that had occurred before my eyes set in I began to feel sick and turned off the television. The image of the victim's face stayed in my head. He had been young, probably no more than 20. Now he was dead, his two decades of life gone with the pull of a trigger, his entire existence made meaningless save for the statisticians. I wondered how his parents, if they were still alive, would react. I cried. Then I got angry.1

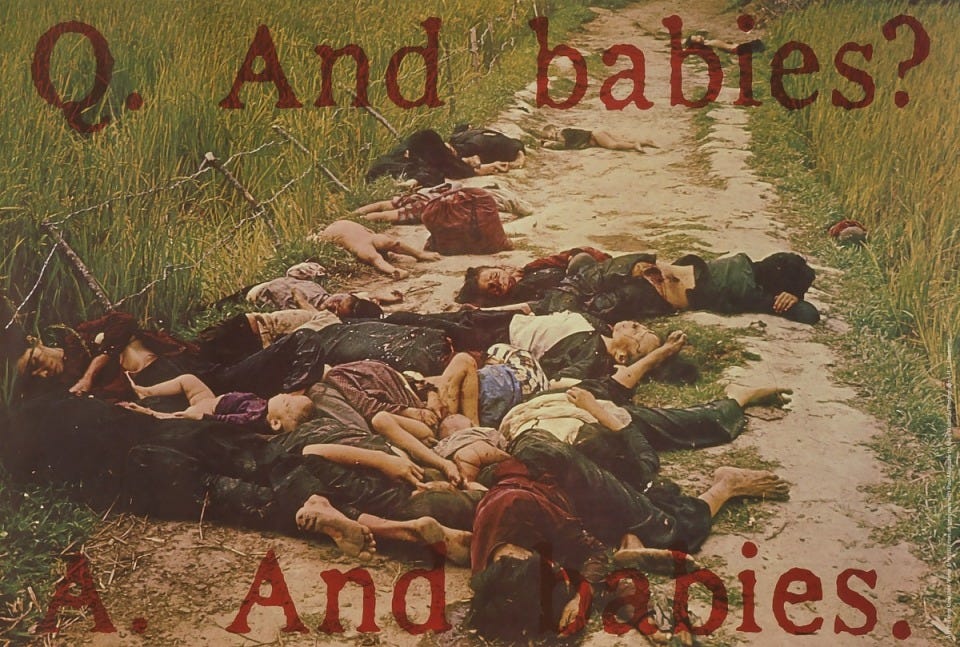

The biographical record on Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr, contains no similar flashes of moral lucidity. While the terror bombing of Vietnam sparked campus rebellions in the US, Biden was busy admiring his own sports coats. His feelings were contempt for protestors and desire to avoid the draft. In 1982, the Israeli war in southern Lebanon shocked even Ronald Reagan, a man who once boasted that the US could flatten Vietnam and paint it with parking stripes. But Biden, by then a Senator, told Menachem Begin he should kill more civilians. Begin was forced to clarify that, although civilians casualties did regrettably occur, “it is forbidden to aspire to this.”

The moral is this: even compared to other politicians, Biden is particularly indifferent to high-tech slaughter. Do individual differences like this matter like this matter? With Blinken, the answer appears to be: no.

Blinken, just as much as Biden, has been a conscious and often eager participant in the Israeli genocide in Gaza. Before you get hung up on the g-word, rest assured that Blinken is not one of those people who think the word should only apply to the Shoah. He is not the kind of person who would say something like: if there had really been a genocide of X group, why did Y genocidaires leave Z percent of X group alive? Nor is he one who thinks that genocidal intent is hard to define. In his 2022 speech at the national Holocaust Museum, Blinken described eight other times since 1945 that the word had applied.

It’s worth reading Blinken’s speech, specifically his account of genocidal intent, to see if it sets off any alarm bells in your head:

The evidence also points to a clear intent behind these mass atrocities – the intent to destroy Rohingya, in whole or in part. That intent has been corroborated by the accounts of soldiers who took part in the operation and later defected, such as one who said he was told by his commanding officer to, and I quote, “shoot at every sight of a person,” end quote – burn villages, rape and kill women, orders that he and his unit carried out.

Intent is evident in the racial slurs shouted by members of the Burmese military as they attacked Rohingya, the widespread attack on mosques, the desecration of Korans.

Intent is evident in the soldiers who bragged about their plans on social media…

Intent is evident in public comments by Min Aung Hlaing… [who] said this, and I quote: “The Bengali problem was a longstanding one that has become an unfinished job… The government in office is taking great care in solving it.”

Intent is evident in the preparatory steps that soldiers took in the days leading up to the atrocities. In the village of Maung Nu, for example, soldiers started by confiscating Rohingyas’ kitchen knives and machetes. Then they imposed a curfew.

Intent is evident in the military’s efforts to prevent Rohingya from escaping, like soldiers blocking exits to villages before they began their attacks…

Percentages, numbers, patterns, intent: these are critically important to reach the determination of genocide. But at the same time, we must remember that behind each of these numbers are countless individual acts of cruelty and inhumanity.

Does the word genocide, as applied not to the massacre of Rohingya but to the desecration of Korans in Gaza and the boasts of IDF soldiers on social media, still make you uncomfortable? Consider the results of a survey by the echt-establishment Brookings Institution, which asked 750 Middle East experts to describe Israeli actions in Gaza. 41% said “major war crimes akin to genocide,” 34% said “genocide,” and 16% said “not akin to genocide, but still major war crimes.” Room for semantic disagreement perhaps, but unquestionably the kind of thing that should make Blinken worried, if he still has a soul. And yet, we learn that Blinken has not only failed to stop the piling of more human bodies into Rothko-shaped mass graves. He has actively facilitated the slaughter, again and again.

Even more than the rest of American politics, foreign policy is carefully shielded from democratic argument, much less control. Jake Sullivan is not only unelected; his appointment did not even require approval by the Senate. Most Americans would not recognize his name. All this being said, there is no question that the exceptionally compact and elitist foreign policy establishment has on occasion had to respond to popular pressures.

As Noam Chomsky wrote in 1982, Establishment complaints about “the Vietnam syndrome” were really complaints about “the reluctance on the part of large sectors of the population of the West to tolerate the programs of aggression, subversion, massacre and brutal exploitation that constitute the actual historical experience of much of the Third World, faced with ‘Western humanism.’” Reviewing Chomsky for the Harvard Crimson, none other than Antony Blinken singled out this point as “the most frightening—and most effective” in the entire book.

It took years for the Vietnam Syndrome acquire a mass character. The overwhelming majority of Americans supported the war when, in April 1965, a group of artists and writers including Mark Rothko signed a full-page advertisement in the New York Times imploring “all those who wish to speak in a crucial and tragic moment in our history, to demand an immediate turning of the American policy in Vietnam to the methods of peace.” Sixty years later, the message echoes. Those who claim to oppose the war can practice degrading contortions to convince themselves and others of the world-historical significance of this or that anonymous leak. Or they can try to expand the sectors of the population which are reluctant to tolerate US support for aggression and massacre. Rothko’s paintings still haunt us. So should the slogan to which he signed his name in April 1965: “End Your Silence.”

Around the same time, elsewhere in the Ivy League, Barack Obama identified himself with “the more sensitive among us,” who “struggle to extrapolate experiences of war from our everyday experience, discussing the latest mortality statistics from Guatemala…”

I continue to be grateful for the clarity and moral conviction you write with. It’s so hard to have the energy to be this angry yet still take the time to write intelligently about what is happening, so thank you