US Labor and the Gaza War (2): Historical Perspective

Are we doomed to repetition? It’s something I worry about.

This is the second part of an essay that I tried and failed to publish in the first half of 2024. For the first part of the essay, and the backstory, see here.

The Current Moment in Historical Perspective

Joe Biden, “the most pro-labor president in history,” pursued a broad program of national security industrial policy as well as an aggressively militarized foreign policy. This is not the first time that US labor has confronted such a situation. Both world wars were important moments in the forging of a relationship between labor leaders, the Democratic executive branch, and corporatist business executives. But while the post-WWI period saw the rollback of both the military-industrial complex and the tentative experiment with labor-capital-government cooperation, something different happened after 1945. For one thing, there was no post-war depression. There was, once more, a post-war strike explosion followed by backlash (Taft-Hartley). But there was no destruction of existing industrial unions as had occurred in the early 1920s.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, 1947: “It may be necessary to bribe the labor movement to take part in the struggle against Communism. Whatever else may be said about a ‘permanent war economy’ at least wages are high [and] employment is full.”

Perhaps most importantly, there was no actual return to peace. Instead, a new condition emerged, which militarists and their critics alike called “semiwar.” To the men (and it was mostly men) who dreamt up the permanent private military-industrial complex, labor had a crucial role to play. Domestically, the economic effects of military spending would help build consent for the Cold War among labor, at that time a crucial electoral constituency for the Democratic Party. As the exemplary Cold War liberal Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, wrote in 1947, “it may be necessary to bribe the labor movement to take part in the struggle against Communism. Whatever else may be said about a ‘permanent war economy’ at least wages are high, employment is full, and the economy is relatively stable and productive.” By the beginning of 1950—before the outbreak of the Korean War—Schlesinger was fighting within his organization, Americans for Democratic Action, for a de-emphasis of domestic issues in favor of a focus on supporting a colossal program of rearmament. Not until the fall of LBJ in 1968 would any important AFL-CIO union say a word against US militarism.

Are we doomed to repeat this sequence? It’s something I worry about. But the material importance of military spending to American capitalism is qualitatively lower than it was during the Cold War. In 1965, at the outset of the Vietnam escalation, the BLS estimated that defense-generated employment in the private sector came to 2.1 million jobs, or around 4% of total private employment.1 By the peak of the war boom in 1968, another 1.5 million private defense jobs had been created, bringing defense-generated employment to over 6% of total private employment. Put another way, more than one out of every four new jobs created between 1965 and 1968 was the result of increased military spending. Today, the Russian warfare state devotes 6% of its GDP to armaments; In the US between 1946 and 1979, military spending averaged 7.7% every year, or 7.2% if you exclude the years of hot war in Korea and Vietnam. Thus, by one important measure, there were decades when the US economy was more militarized in “peacetime” than Putin’s Russia is after two years of conventional war.

One out of every four new private sector jobs created between 1965 and 1968 was the result of increased military spending.

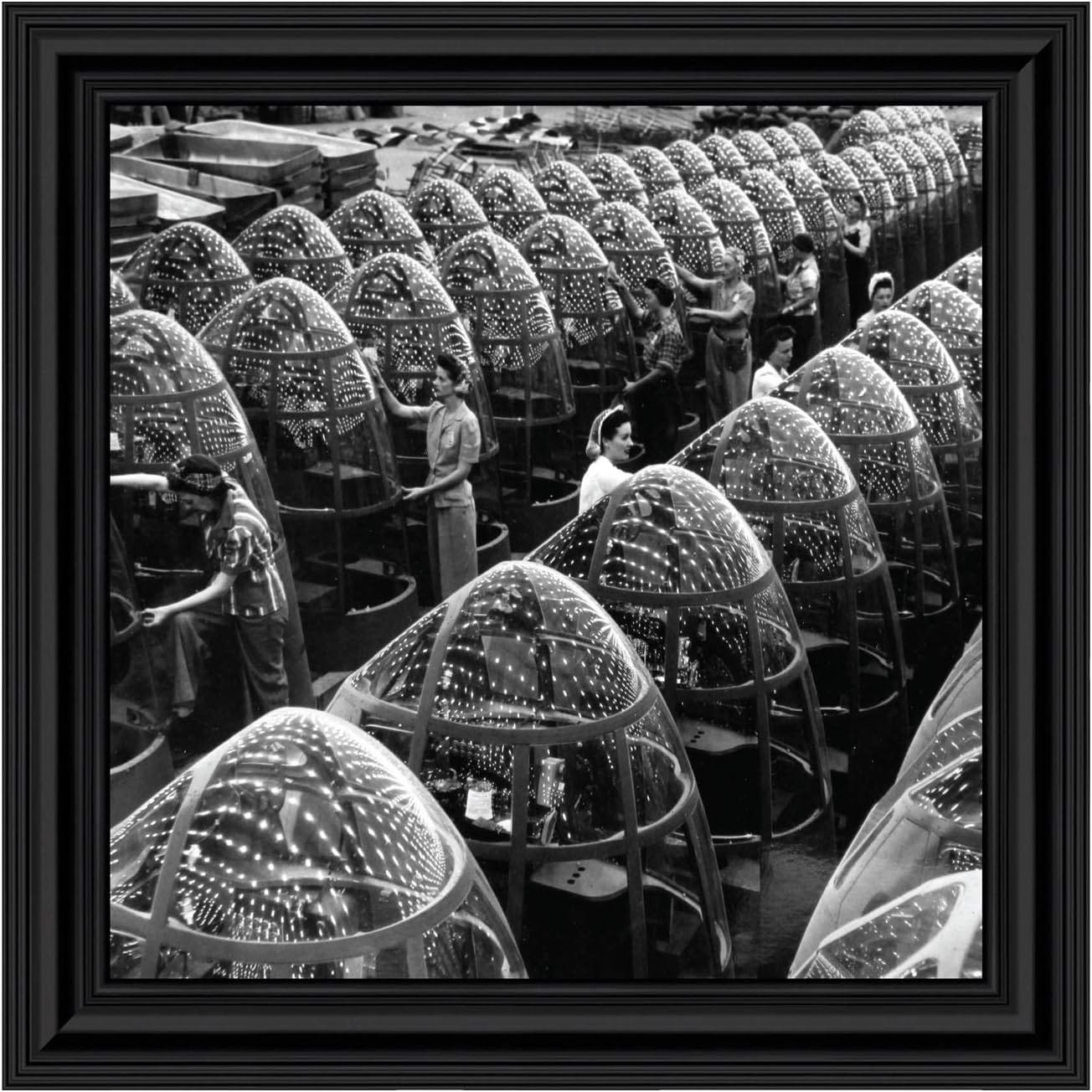

Dramatic effects were still visible during the rearmament associated with the Carter/Reagan “Second Cold War.” Defense-generated private employment rose from 2.2 million in 1980 to 3.2 million in 1985, or from 3% of total private employment to about 4%. As in the Vietnam boom, this employment increase accounted for a significant share of all new job creation. This was especially true in the manufacturing sector, whose civilian branches were suffering depression-like conditions. Between 1980 and 1985, American manufacturing shed almost one million jobs. But, in the same period, defense-generated manufacturing employment increased by 600,000. Thus, anyone who still had a factory job in 1985 was far more likely to be defense-dependent than his pre-Volcker shock equivalent.

The situation today bears almost no resemblance to the Cold War decades. According to the private National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA), the contemporary defense industry employs just 1.1 million workers, about eight-tenths of one percent of total private employment. Equally importantly, defense-related employment does not appear to be growing under the sign of Bidenomics. According to the NDIA, the employment total was the same in 2023 as it had been in 2021 “that number is remaining flat.” Even if we look at the “aerospace and defense” sector, a concept which includes the manufacture of civilian aircraft, employment appears to be virtually unchanged compared to pre-pandemic levels.

If we zoom in on specific projects, even quite large undertakings, we get a clear sense of how minimal the employment effects tend to be. What about the new ammunition plant being built by General Dynamics in Mesquite, Texas? The New York Times reports breathlessly that “The plant could help turn the area into an industrial hotbed of well-paying jobs.” How many? According to the Times, the factory is expected to initially employ 125 people, rising someday to perhaps 300. By comparison, at a single large General Electric plant at the dawn of the Cold War, the number of shop stewards alone would have been over 300.

The stagnation in defense employment is in line with the trend in manufacturing more generally, where employment has grown far more slowly than the economy overall. The result is that the manufacturing share of total employment is lower now than it has ever been. This hardly means that there are no economic consequences. Fixed investment, a pivotal component of aggregate demand, has boomed in sectors like electronics. The production of defense and space equipment has grown much more rapidly than overall industrial production. But these are the effects you’d expect from stimulating capital-intensive sectors, not from a full employment program.

The point is worth insisting on, given the misleading statements which appear not just in political rhetoric but in the respectable media. The New York Times headlines a story “Factory Jobs Are Booming Like It’s the 1970s,” which turns out to describe a net addition of 67,000 manufacturing jobs. Considering that the net decline between 1979 and the present is 6.5 million, it’s hard to see how to read the headline except as propaganda. Similarly, the point of describing a new ammunition plant as a “hotbed of well-paying jobs” is to suggest that politicians “whose constituents benefit directly from continued American [military] aid to Ukraine” should, for that reason, vote a certain way on American foreign policy. The implication: if politics is not already a mechanical response to immediate economic interests, it ought to be. Any space to debate the real meaning of community “economic interests” vanishes in the hype.

To suggest that politicians whose constituents benefit directly from military spending should support higher military spending is to suggest that politics ought to be a mechanical response to economic interests.

Against this, we should continue to insist on the importance of the sectors which employ most workers. This hardly means dismissing manufacturing workers. To the contrary, the unorganized majorities in factories need the labor movement more than ever, and unionized manufacturing workers have been crucial to revitalizing UAW.

But we need a realistic sense about the shape of the entire economy. To restore the manufacturing share of employment to its pre-2008 level would mean adding 3 million new jobs. To go back to pre-China Shock levels, you’d need 7.5 million. In a 2020 EPI proposal, which can stand as an example of what a politically unconstrained left-Bidenomics might accomplish, the promised result is 2.5 million new manufacturing jobs. There’s simply no way that industrial policy–military or otherwise–can provide good jobs to anything but a small minority of Americans.

Regardless of how many manufacturing workers there are, their employment and economic security should not be hostage to geopolitical contingencies or the vagaries of military appropriations. Finally, everyone, including manufacturing workers, will be better off if our factories build the things that can make life better at home, rather than things destined at best for the stockpile and at worst for the slaughter-bench.

Everyone, including manufacturing workers, will be better off if our factories things that make life better, not things destined for the stockpile or the slaughter-bench.

Beyond employment effects, the Cold War AFL-CIO was also defined by a specific ideological constellation which no longer exists. Even when defense-generated employment was much more extensive, there were significant non-economic forces pushing American labor leaders and (with varying degrees of commitment) rank-and-file workers towards support for Establishment foreign policy. These included the repression of dissenters; the weight of Catholics and Slavs in the composition of the working class; bad experiences with Stalinist trade union rivals; and sincere internationalism. For labor leaders, moreover, the prestige of becoming a diplomatic asset compensated for lack of power at home. But today’s hawkish elites hardly need labor ambassadors the way they did during post-1945 reconstruction. Workers and union leaders may still be moved by appeals to the national interest. There are certainly popular ideologies which justify the killing of poor people living in “terrorist” states, and we can expect new attempts to forge an integral Sinophobic worldview. But compared to the organic links between domestic anti-communism and the Cold War, this is weak stuff—at least so far.

These BLS estimates include employment generated directly in defense industries as well as indirect employment generated in industries providing inputs to defense industries. There is no attempt to include the “military Keynesian” process in which the incomes produced by defense spending subsequently induce economic activity in other sectors via multiplier or accelerator effects. The BLS numbers can thus be considered as understatements of the real magnitude of defense-generated employment.

Great piece. Since defense production is largely privately owned, there is not a good way around building up the military-industrial complex if security needs for a changing global order demand it. Automation and robotics means fewer workers are needed, so labor can maintain more independence than in the past.