There is a half-mile radius in Laos where the US once dropped 88 500-pound bombs and “at least 37,289 bombies.”1 Forty years later, farmers still found canisters labeled: “Special firework. Handle carefully. Keep fire away. Pine Bluff Arsenal.” In December 2023, a journalist working for the Washington Post found the remnants of 155mm shells launched by the IDF against the town of Dheira in Southern Lebanon. Two were marked “PB-92”—Pine Bluff, 1992.2 And another code: “WP.”

The canister in Laos had contained napalm. The shells in Lebanon, white phosphorous. Both are ways of burning people alive. As military officials and their journalistic retainers never tire of pointing out, there are legal uses of white phosphorus: to create a smokescreen to conceal troop movements, to illuminate the night sky. But US military manuals clearly contemplate the weapon’s other, illegal uses: “Used as a screening, signaling, casualty-producing, or incendiary agent.” During the Iraq War, the Pentagon did not deny using white phosphorus “as an incendiary weapon against enemy combatants.” A participant in Operation Cast Lead (2009) said Israeli soldiers fired white phosphorus “Because it’s fun. Cool.”

Even in April 1965, before there was much of an antiwar movement, Time described “napalm bombs that incinerate whole villages” and “white phosphorous shells that burn a man to the bone.” White phosphorous, some say, is worse. Someone who had visited a Saigon children’s hospital told Congress that WP “is more terrifying because it does not extinguish as readily as napalm. So long as the surface receives air it will burn.” Frank Harvey—a pro-war writer—agreed that “this stuff is even more vicious than napalm.” In a civilian hospital, Harvey “saw a man who had a piece of white phosphorous in his flesh. It was still burning.”

Still burning: the image recurs. In Dheira, evacuees returned to homes which were “still burning.” The chronicles of earlier bombardments describe “wedges still burning when children dug them out of the sand,” “streets and alleyways littered with…still-burning wedges,” “patients still burning when they arrive at hospital.” In 2009, in Gaza, Sabah Abu Halima watched her husband and four of her children “melt away.” Her own wounds, said her doctor, “were deeper and wider than anything I had seen…smoke continued to come out of them for many hours.” Sabah told Amnesty International: “I was on fire. Now I am still burning all over.”

Who would not rather forget all this? Yet the image has haunted poets. Yusef Komunyakaa (a combat veteran) wrote about “a girl still burning inside my head.” Denise Levertov imagined white phosphorous giving an account of itself: “I am the snow that burns.” The incendiary monologue continues:

The white phosphorus capital of the hemisphere

From Laos to Lebanon, the signs on the shells point back to the Arkansas Delta, to Jefferson County, where the Pine Bluff Arsenal sits eight miles from the eponymous town. On the internet, the trail will lead you to the website of “America’s Arsenal,” with the tagline: “Every munition we make carries the PBA name on it and is marked with quality!” PBA is “a world leader in the design, manufacture and refurbishment of smoke, riot control and incendiary munitions, as well as chemical/biological defense operations items.” It is the only place in the Western hemisphere that fills white phosphorus shells. Those discovered by the Post, like fragments identified after past Israeli attacks, were produced decades ago. PBA continues to produce new WP munitions, some of them for export.

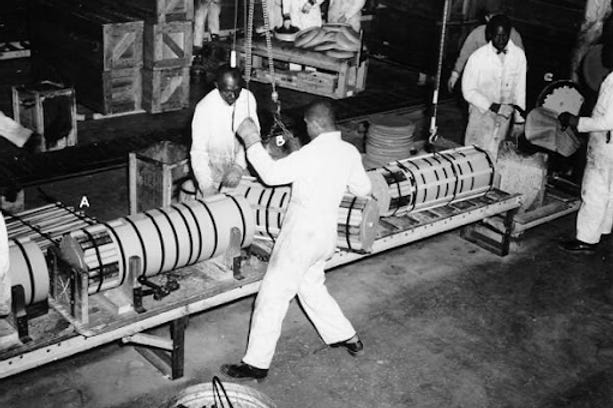

White phosphorous is one thing you can put into those famous 155mm shells (you can also put it in other containers). The chemical liquid, derived from phosphate rocks, is delivered at Pine Bluff, where it is stored or packed into steel shell casings. Each hermetically sealed shell contains an explosive charge plus 116 felt wedges soaked in white phosphorus (some of the technical literature says the felt is “impregnated” with the liquid). When fired, the charge ejects the wedges, which ignite upon hitting the air and scatter indiscriminately over the area of a football field.

Above: “My name is a whisper of sequins…Each of them is a disk of fire.” (Denise Levertov)

The Pine Bluff Arsenal dates to the period just before Pearl Harbor, when a congressman “aware of the economic benefits of such an installation on the state’s depressed economy” brought the project home to his constituents. In 1940, Arkansas’ per capita income was 43.7% of the national average. By 1950, it was 59.8%. “World War II,” one historian has written, “set in motion the most important economic

change in Arkansas since the introduction of cotton production a century before.”

The War Department encountered resistance from “some business and plantation owners,” one of whom warned that the Arsenal would subvert the social order “by reducing the farm labor workforce” and “by raising wages [and] possibly forcing plantations and some businesses into bankruptcy.” They still held a monopoly on official violence, but the planters did have something to worry about. In 1940, the population of Pine Bluff was 21,000. The Arsenal alone would employ over 9,000. The labor market drained further as Arkansans migrated en masse to even better jobs in other states.

The Arsenal employed men and women, black and white. The local paper gushed that “the walls of prejudice in industry are crumbling.” Perhaps white people thought so, but it went without saying that the factory (like all of Pine Bluff, not to mention the US Army) was segregated, with black workers shunted into dirtier and more dangerous jobs. This dynamic has a special meaning when “dirty anddangerous” meant explosive: at Pine Bluff, 15 people died from accidents during WWII.

It would take another post to catalog all the weird things once made or stored at Pine Bluff. The Arsenal originated under the Chemical Warfare Service, making mustard gas in WWII and “binary chemical weapons” under Reagan. On-site “igloos” held stockpiles of sarin, etc, and chemicals captured from Nazi Germans. In the 1960s, the Arsenal loaded munitions with a hallucinogen called BZ. Pine Bluff was a headquarters of our biological weapons program, suspended in 1971. When activists mobilized against stockpile incineration, they found that:

The Army, back so long ago, had indeed chosen its sites well. An insulated community that has perceived the Army and its local Depot as an economic patriarch for half a century or more is not prone to critical reevaluations of how that Army or that Depot conducts its business. To question the modus operandi of the Army was to assault the town itself.

Even in this world, “Pine Bluff was especially hard-core.” Activist Craig Williams was “threatened with bodily harm there on several occasions.” In 2012, the local newspaper said: “Many consider the partnership PBA enjoys with its surrounding community to be the strongest of all the nation’s military posts.” An activist recently reported “the arsenal has a very small staff and that jobs are hard to come by in the area, making it nearly impossible to compile further information.”

Late last year, PBA received two SkyCop units, an overnight surveillance setup you might see in a Walmart parking lots. The Arsenal newsletter linked the SkyCops to “some concerning information circulating online about the Arsenal late last year.” Articles linking Pine Bluff to Israeli white phosphorous had appeared throughout December. The possibility of antiwar protests were discussed on Arkansas subreddits. The “Coast Guard/Department of Homeland Security picked up on it” and sent out a call to cop networks. The Shelby County (Memphis) police offered two machines, and the Coast Guard patched them through to the Arsenal. When it was all done, the Commander of the Arsenal gave a certificate to the Memphis cops.

Does Pine Bluff have a future?

Pine Bluff has less to fear from protestors than budget cuts. The Arsenal newsletter declared in 2016, “as PBA enters its eighth decade,” that it “continues to deliver the biggest economic boon in the county’s history.” But the boon is not what it used to be: there were over 9,000 employees in 1943, 2,000 in 2010, and just 600 today. As of late 2022, “closure isn't out of the question.” Beyond generalized austerity, there was the question of what the Arsenal was for:

After nearly seven decades, chemical weapons storage at Pine Bluff Arsenal ended in November of 2010. Two years following, the Pine Bluff Chemical Activity and Chemical Agent Disposal Facility closed operations and with it the anchor mission to the Arsenal. Today, there no longer exists a completely unique mission requiring specialties in chemistry and material security.

By 2016, PBA was “operating at 57% capacity that it was in 2009.” Pine Bluff had encountered this problem more than once before, including when Nixon shut down bioweapons. One solution has always been to come up with “an entirely new mission set.” Since 2016, Arkansas Senator John Boozman—who sits on the Appropriations Committee—has made the Arsenal “a top source” for chemical-biological PPE.

Another solution is to advocate more effectively for the existing mission sets. The Arkansas Economic Development Commission (AEDC) emphasizes the need “to protect Pine Bluff Arsenal’s unique production assets from international alternatives.” One of those assets is white phosphorous. In 2017, PBA launched a new production line, packing WP into 120mm M929 mortar rounds. According to the project engineer: “The new WP Line 5 uses 10 workers, the older lines used approximately 25 to 30…this is our most complex production line with lots of different systems communicating with each other.”

The Arsenal looks like a good place to work. Since 1969—when a war boom met a wave of public worker organizing—employees have belonged to AFGE Local 953. Their contract enshrines the “right to expect and pursue conditions of employment promoting and sustaining human dignity and self-respect.” Wages are “80% higher than the regional average. Amenities include: gym, stocked ponds, cabin rentals.

But a good place to work is not always a nice place to live. Once the largest city in the Arkansas Delta, and the fourth largest in the state, Pine Bluff is now only the 10th largest in the state and shrinking fast. Decades of “social stigma and environmental legacy of producing poisonous chemicals” have not helped. But economic activity that came with the poison was a trump card, as the military freely acknowledged. In the late 1980s, the Army was “still cleaning up…DDT, heavy metals such as arsenic and barium, and other toxic compounds.” Despite this, the base commander was confident residents would “support the new binary weapons program because it will add up to 500 jobs to a stagnant local economy.”

In the 1980s, Pine Bluff was “dead last” in Rand McNally’s list “of desirable places to live.” In 2022, a website ranked it “America's most miserable city.” One Pine Bluff City Council Member responded: “I agree with that. I hate that from the bottom of my heart.” By some metrics, it is the most unsafe community with between 30,000 to 100,000 residents in the country. More than a decade ago, one local cop was willing to call it: “Pine Bluff has just sort of faded away.”

So what would happen if they closed the Arsenal? This was the question that the local government put to an economic consultant who seems to specialize in military-industrial impact studies (they also did one for the state of Florida). The consultants found “an estimated 951 direct, indirect and induced jobs created by the industries at the Arsenal.” Their presentation laid out the social life of multiplier effects: what percent of Arsenal employees live in the county (62%), what percent of the plant's supplies are bought in-state (60%), how often does a dollar change hands before leaving the county (twice). I don’t know how many of Jefferson County’s local notables think of themselves as Keynesians, but they know that the closure of the Arsenal “would cause a ripple down effect.” Like so many professional economists, they reach for military imagery: the “fallout” would be like “a bomb going off.”

To serve God and Wal-Mart, and Raytheon

Closing Pine Bluff Arsenal might devastate Jefferson County. But “virtually every corner of Arkansas has at least one aerospace or defense employer.” According to lobbyists, the sector employs just 10,000—less than 1% of total employment. Arkansas has way more people locked in its prisons than working in its military industry. More impressive is the claim that Arkansas exports $1.5 billion in defense/aerospace output each year—which would make the state comparable to the Netherlands as a player in the international arms trade.

The hub is in East Camden, 70 miles southwest of Pine Bluff. The former Shumaker Naval Ammunition Depot, which once made Sidewinder missiles, has been converted into a vast (5.4 million sq. ft.) privatized industrial park, shared by contractors including 3 of the top 5 (Lockheed, Raytheon, General Dynamics). One Redditor says: “Camden has tons of jobs at the weapons plants. That being said it is a horrible place and I don't know why anyone in their right mind would want to live there.”

East Camden’s role in supplying Ukraine has received national attention, but another export market has a deeper place in the hearts of the Arkansas’s political class. Asa Hutchinson (governor from 2015-2023) visited Israel four times, with funding from the private Arkansas Economic Department Commission. He claimed that an Israeli prime minister (presumably Naftali Bennett) once told him to “tell the people of Camden and Arkansas, that you’re saving thousands of Israeli lives by what you produce.” Hutchinson signed a law which “prohibits state agencies from contracting with companies that participate in the boycott of Israel and reduces their fees by 20% if they don’t sign a pledge to oppose BDS” and said that if he were president, he would use the US military to attack Hamas directly. Likewise, Sen. Boozman co-sponsored legislation to make “it a federal crime for Americans to encourage or participate in boycotts against Israel and Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories.” This month, he introduced the resolution condemning “any action by the Biden administration” to withhold or even “pause” arms for Israel.

Historian Abdel Razzaq Tikriti said recently “it would be madness to think that a Christian evangelical in San Antonio, Texas has a material interest in the colonization of Palestine." So it’s worth mentioning that 79% of Arkansans adhere to some form of Christianity, and that of the state’s Christians, two out of three are Evangelical Protestants. But an ideology, if it is powerful enough, will establish its reflection in the material life of a community; this objectivity can, in turn, make the ideology that much more powerful. But the economic interest does not automatically make itself felt in political consciousness. “If you ask the average Arkansan,” laments one congressman, “they probably would not know that the single biggest export that we have is in the aerospace industry.” And why should they, when less than 1% of Arkansans work in the industry?

What cements the complex is not the mere existence of jobs but the way in which “national security” can be experienced simultaneously as an economic asset and a way of feeling, as a means to material security and an end in itself. The local Lockheed site may only employ 1,000, but it sits at such an important intersection that the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff took the time to visit and remind Republicans that arms transfers to Ukraine “will not only help in the fight against Russia, but also support jobs in their districts.” At the high school football game where you once cheered on The Varmints, you now cheer for The Rockets. A muralist comes from California to paint murals depicting “defense workers against a backdrop of streaking rockets, missiles and fighter jets.” As you can recognize yourself in the murals, you can watch TV as something more than a spectator: the “weapon systems we get to watch on CNN so intently come out of Camden, Arkansas.”

Back in 2017, plenty of Arkansas’s missiles ended up in Israel. But, on the eve of a foreign trade trip, Gov. Hutchinson pointed out “There are currently no Israeli companies operating here.” Thanks to Hutchinson and his successor, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, that is no longer true. Last summer, they brokered a deal for a new plant in Camden: a joint venture between Raytheon and Rafael, the third-largest Israeli defense firm. The factory will build rockets for Israel’s Iron Dome and a variant to be used by the US and other allies. As with NATO standardization in the last century, a partnership like this allows US and Israeli security concerns to merge. The technical fact of production to “US and Israeli requirements” gives rise to the feeling that Americans should be proud to work “ensuring the security of the citizens of Israel and America.” South Arkansas is proud to “serve the U.S. Marine Corps and our allies,” which now means “direct support for Israeli Defense Forces.” As the Rafael executive who attended the groundbreaking said, “local production…will strengthen the partnership while safeguarding the interests of all sides.”

The military-industrial complex doesn’t just reflect and reproduce nationalism. It also fashions a domestic basis for internationalism (at least, a certain kind of internationalism). Last week, Matt Yglesias rediscovered a problem that the architects of the first Cold War knew well: “Foreign policy is much more driven by elite consensus than by public opinion,” but major shifts in foreign policy require “some level of public buy-in.” There is something superficially strange about a spectacle like Lyndon Johnson barnstorming rural Texas in 1948, accusing his opponent in the race for Senate of being an “isolationist.” But there was a local basis for this high-minded internationalism: the cotton exporters who created the Marshall Plan and the military-industrial complex which had already transformed Texas.3 When Asa Hutchinson, an alumnus of Bob Jones university, runs around raving about Trump’s “isolationism,” I think of LBJ. Through what alchemy has this anti-trans, anti-abortion creationist managed to receive such flattering tributes from the Council on Foreign Relations?

An Arkansas Ideology?

At Naftali Bennett’s “International Smart Mobility conference,” then-governor Hutchinson compared Arkansas’s largest private employer to the “start-up nation”:

Something I am concentrating on is smart mobility, from autonomous vehicles to drone deliveries, which Walmart is also engaged in, and Israel has startup companies in all of those areas. One of the things I am taking back with me is how Israel has become a leader in innovation and invests in new technologies that benefit the entire world. We must invest more.

Hutchinson signed, in both Hebrew and English, “a Memorandum of Understanding with the Israel Innovation Authority.” He created the Arkansas Council on Future Mobility, chaired by Cyrus Sigari, a “an aviator, investor and entrepreneur” alleged to be among “the world's foremost experts on the future of mobility.” Sigari’s company UP Partners is “an early-stage venture capital firm in California that invests in technology companies,” specially advanced aerial mobility [AAM] and electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL). He brought the UP Summit, said to be “the Davos of mobility,” to Bentonville. Sigari’s dream is that Arkansas and Oklahoma will “become the Silicon Valley of transportation and logistics.” Hutchinson agrees: “I have seen enough of space-age mobility and technology in Arkansas to know that drones and autonomous vehicles are no longer the stuff of science fiction.”

Arkansas’ leaders point to legislation “that allowed companies to test autonomous vehicles in Arkansas”; Walmart “operationalize[d] drone delivery in four stores in Northwest Arkansas”; Gatik “pioneered the use of autonomous refrigerated box trucks”; some bloc of companies has “driven more than 200,000 autonomous miles in the state” and once “removed the safety operator from the driver’s seat”; EV company Canoo picked Bentonville for its HQ. The corporate roll-call at the cutting edge of logistics includes Wal-Mart, Tyson, ArcBest, JB Hunt, Transplace, Zipline, and DroneUp. The aerospace/defense sector employs just 10,000 statewide but “85,000 Arkansans are employed in the distribution and logistics industry.” Both state flagships offer degrees in supply chain management.

Who knows how much weight this can bear. But the vision brings together key features of our present and near-future. High-tech mass murder and next-day delivery; the dream of the open shop and the dream of the driverless truck; anti-state ideology with limitless federal money; Trump and anti-Trump GOP; evangelicals and the woke Pentagon. The US and Israeli tech sectors, always in need of hype, will have a new story to sell. There might even be a way to save the poor relations in the Delta, by locating a new “Joint Logistics Distribution for Chemical and Biological Defense” at Pine Bluff. This capacity which could ultimately “enable rapid deployment of military hardware to global destinations via the Arkansas surface transportation network” and “regional air opportunities.” The “long-term redevelopment program” also explores “the advantages of privatizing energy at Pine Bluff Arsenal.”

Another synergy is obvious. One day, the US-Mexico border could be droned and surveilled by the same Arkansan defense-logistics complex whose driverless trucks connect Wal-Mart outlets backwards to the Tyson chicken plants where wages are repressed by intermittent ICE raids. The defense workers might use school vouchers to send their kids to Christian schools, to be trained in apologetics and aeronautical drafting. On their way to clock in at the Iron Dome factory, US citizens (with security clearances) can drive past agricultural workers, working outside all day, without papers. They probably won’t even notice the drones loitering above the prison farms, where unpaid “hoe squads” work the soil of former plantations for the benefit of Tyson and Walmart. Different legal regimes—different lifeworlds of mobility and arrest—for racially-differentiated groups sharing the same haunted land. There used to be a word for that, but by this point certain historical analogies are no longer permitted.

The latter being a heartbreaking name given by Laotians to the bomblets released by cluster munitions. Of 270,000 “bombies” dropped on the country, an estimated 30% failed to detonate, leaving around 80,000 as permanent dangers to generations of Laotians.

The third shell said “THS-89,” indicating the 1989 vintage from the now-defunct Lousiana Army Ammunition Plant, owned by the government and operated by Thiokol (since absorbed by Northrop Grumman). Israeli use of Thiokol shells has been documented in earlier attacks. Since the Louisiana AAP is out of operation, I focus here on Pine Bluff.

Just before the decision to build the Pine Bluff Arsenal was built, LBJ brought home a similar prize: a new naval air base at Corpus Christi, constructed on a cost-plus basis by his patrons Brown & Root. Within the FDR administration, this piece of pork was explicitly aimed at “crystalliz[ing] a new leadership in Texas” around LBJ, following the defection of right-wing Texas Democrats in 1940. In the 1948 Senate campaign, LBJ canvassed rural towns using a helicopter, provided to him by his campaign donors Bell Aircraft. Whenever possible, LBJ arranged to be introduced on the stump by a veteran with a missing limb.

Never liked that state.