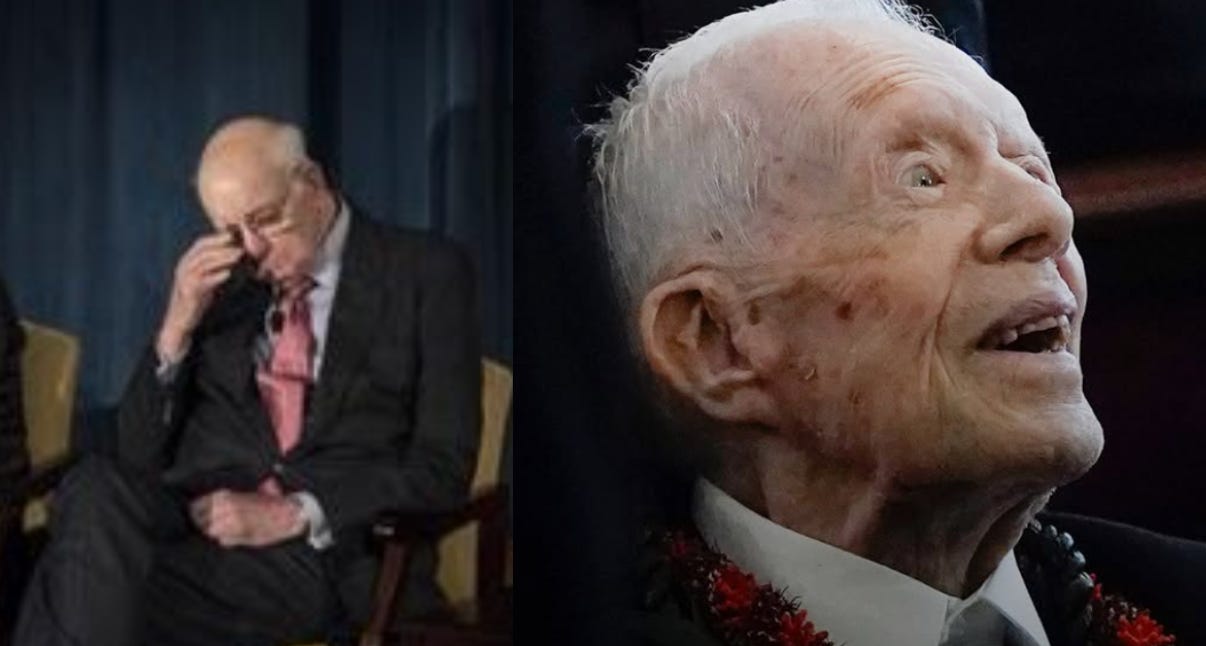

Jimmy Carter, 1924-2024

As an individual, Jimmy Carter stood as a rebuke to our venal and heartless political class. As a politician, his private virtues proved to be public vices.

Jimmy Carter was admired by so many people because there have been so few people like him. Even those who take a dim view of his presidency or have little sympathy for his Christian worldview have found Carter to be almost saintlike. He wore clothes from the dollar store, built houses for charity, and always arrived on time.

He spoke forthrightly on subjects like Israeli apartheid and American inequality. On the latter, he sounded like Bernie Sanders, for whom he voted in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary. When Carter entered hospice care almost two years ago, one progressive leader (from the Working Families Party) called him “ahead of his time” and another (from MoveOn) hailed his “legacy of progressive people-first policies.”

Yet it was Carter who ushered in the neoliberal policy regime that has shaped our age of inequality and provoked bitter opposition from the Sanders wing of the Democratic Party. In fact, as we consider the former president’s legacy, we cannot disentangle his attractive personal qualities with his much more fraught neoliberal policy legacy.

His private virtues proved to be public vices. The same thrift and moral seriousness that make Carter stand out also fed into his austerity policies — which proved to be political suicide in 1980 and, in updated versions ever since, have stunted the lives of millions of Americans and sustained extreme social inequality, which looks increasingly incompatible with our democracy.

Nearly everything you might associate with Reaganomics was actually underway by the time Carter left office: deregulation of energy, transportation, communications and finance; higher military spending alongside reductions in support for low-income Americans; punishingly high interest rates; trade expansion; rapid deindustrialization; and accelerating de-unionization. Carter was hardly the only force behind these outcomes, but he contributed intentionally to each.

By 1984, Stuart Eizenstat, Carter’s top domestic policy adviser, could already describe the former president’s most important legacy as “taking the Democrats into the post-New Deal era.” This meant “supporting fiscal moderation and less government intrusion in the economy — a philosophy of government that some now describe as ‘neo-liberal.’”

It is common to separate Carter’s laudable personal qualities from his presidency, which even admirers tend to consider a failure. But his neoliberalism was bound up with his temperament and value system. Think about the different meanings of “austerity.” In political economy, the word refers to budget cuts and wage restraint. In personal life, austerity means the moralization of sparseness, the practice of sucking it up and doing without.

It is no accident that the image that has stuck is Carter wearing a sweater. He did not actually wear one during the 1979 “malaise” speech, just like he didn’t actually say the word “malaise.” But he had worn a sweater in an earlier speech, and that was the general vibe in the malaise speech as well. To be sure, saving energy is better than wasting it. This became especially clear when Reagan gleefully ripped the solar panels off the roof of the White House. But ordinary Americans could hardly transform the energy sector through their personal behavior. The social critic Christopher Lasch reminded the White House that during the 1974-75 energy crisis, “many Americans patriotically turned down their thermostats in the winter only to be socked with higher fuel prices, justified on the grounds that demand was off.”

Those who see Carter as a moral authority often admire the “crisis of confidence” speech. Kevin Mattson, a liberal historian, wrote a book praising the speech as an anti-consumerist jeremiad that “should have changed America.” But the idea that Americans had it too good was neither unique nor progressive. It was ubiquitous in the 1970s, expressed most frequently by business leaders and right-wing economists who warned that the nation was indulging in leisure and welfare at the expense of “capital formation” and “adequate profits.”

This rigorism clearly informed Carter’s final Economic Report of the President, which called for the investment share of gross national product — already at record levels — to rise even further. This meant that “the combined share of consumption and government spending will have to fall by a corresponding amount.” In practical terms, Carter’s appeals to sacrifice meant squeezing workers and consumers to finance business investment and military buildup.

His most fateful decision came in 1979, when he appointed Paul Volcker as Federal Reserve chair. The legendary central banker, who would serve until 1987, became the most powerful policymaker in the United States (and perhaps the world) during the transition to neoliberalism. As the economist James Tobin wrote in 1982: “Thatcherism may be American policy, too, but its author is not Ronald Reagan. It is Fed chairman Paul Volcker.”

Volcker shared many of Carter’s most admirable quirks. He wore cheap suits, hated corruption, and inherited his father’s strong moral code. Austere morality — which treats waste and idleness as far graver sins than suffering and deprivation — pushed toward austere policy: an interest rate shock that drove unemployment into the double digits and devastated older industrial regions. This program explicitly required breaking the strength of organized labor, whose power to raise labor costs the Fed has long seen as inflationary dynamite. The index of Volcker’s success was that real median earnings were lower in 1999 than in 1979. The index of liberal amnesia is Paul Krugman’s insistence on dating the decline of “strong unions” to 1980.

The most powerful apology for neoliberalism is that there was no alternative. Many people describe the Carter-Volcker recession as unpleasant but necessary medicine. It remains difficult, perhaps impossible, to say what the alternative was, as long as one takes for granted the institutional framework of American capitalism circa 1979.

What we can say for sure is that, at the moment Carter won the presidency in 1976, the future of American capitalism looked wide open. In 1974, a wave of “Watergate babies” were elected to the most liberal Congress in years. Americans may have been increasingly suspicious about Richard Nixon’s version of big government, but they were far more skeptical of private economic power than most people remember. By the mid-1970s, only 20 percent of Americans told pollsters they had “a great deal of confidence” in corporate executives, down from 51 percent a decade before.

When Carter took office in 1976, the future of American capitalism looked wide open.

This made sense, given the decade that had transpired. The Vietnam War intensified suspicion of the military-industrial complex. Watergate was, in part, a scandal about illegal corporate donations. It was followed immediately by an energy crisis and the worst economic slump since the 1930s. Against this backdrop, politicians talked seriously about nationalizing oil companies and directly controlling foreign investment. Following the American defeat in Vietnam, the same Congress which had once rubber stamped defense appropriations now routinely slashed Pentagon budget requests. The debate over national economic priorities, which had been shut off by the Democratic embrace of Cold War rearmament around 1950, now reopened. A thousand proposals for the comprehensive expansion of social services bloomed.

In 1971, one Nixon adviser predicted that “within 10 years, 50% of our industrial production will be controlled by the government.” Five years later, the 1976 Democratic platform called for “national economic planning.” Grassroots activist and nationally prominent leaders scrambled to assemble new coalitions. Their emergent demands — racial justice through full employment, public investment in unionized alternative energy plants — remain urgent today. So does Carter’s willingness, on the campaign trail that year, to propose cutting another $5-7 billion from defense, and to permanently remove US troops from far-flung bases in places like South Korea.

Obviously, none of these ideas survived the turn of the 1980s. But the plasticity of the political moment is, ironically, confirmed in the fact that Reagan’s rendition of neoliberalism was quite different from Carter’s. Instead of austerity, Reaganomics promised the moon: Consumption, investment and defense would all increase together, without any need to worry about the deficit or impose cuts to middle-class entitlements. Taxes could be cut for individuals as well as for corporations. To some extent, these fables of abundance became reality. The consumption share of G.D.P. rocketed to levels unseen since the 1940s, while government spending (defense and non-defense) continued to grow. Predictably, Reagan’s exuberant neoliberalism, which rained government benefits on many constituencies, was more successful than Carter’s counsel of diminished expectations.

In private, Carter’s own economists acknowledged that “eliminating the deficit has no direct effect on inflation.”

Democratic loyalists claimed that Reagan’s political spoils system was at odds with the laws of economic reality. But Reagan’s Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger was on solid Keynesian ground when he said that “you aren’t really adding substantially to your deficit when you add military spending, because jobs are created and investment is stimulated.” Indeed, the econometric model that Weinberger’s Pentagon used to generate estimates of defense-related employment was based on the model designed by Lawrence Klein, a founder of American Keynesianism. Carter’s own economists acknowledged in their internal memos that their vaunted goal of balancing the budget was mostly “symbolic,” since “eliminating the deficit has no direct effect on inflation.”

If there were real political choices to be made in the late 1970s, why did the Man from Plains choose as he did? Carter’s attraction to economic austerity reflected the same formative experiences that produced his personal virtues. “My father was my hero,” he recalled, “and I watched his every move with admiration and a desire to emulate what he did.” James Earl Carter Sr. modeled hard work, piety, time management, thrift and (at least according to his son) sharp but honest business practices.

Carter’s roots in a racially ordered, labor-repressive social world inflected his relationships with key New Deal constituencies.

The Carters shared in the deprivation endemic to the South in the 1920s and 1930s. But if people today think of Carter as some kind of poor white, that is only because they have forgotten how poor nearly everyone in the South was before Taft-Hartley, air conditioning, and the military-industrial complex. As sympathetic biographers have acknowledged, the Carters “occupied the top rung in a hierarchical society.” James Earl Carter, Sr., and his wife Lillian were minor gentry, not poor farmers like the hundreds of black sharecroppers and day laborers whose economic lives they dominated. “It shames me now to talk about it,” said Lillian years later, “but they made practically no money.” In 1936, Franklin Roosevelt received over 87 percent of the vote in Georgia. Carter’s father was among the handful who voted for the Republican Alf Landon. Even the leading Democrats in the region—the men who administered the Southern New Deal on the local level—tended to be employers, terrified that government assistance would weaken their control over black labor (or, as Carter wrote more politely, they “strongly opposed relief payments as an incentive for recipients to reject available farm work.”)

Carter’s roots in this racially ordered, labor-repressive social world would later inflect his relationships with key New Deal constituencies. As corporations fled to the nonunion Sunbelt, he continued to support state-level right-to-work laws. Throughout the 1970s, the A.F.L.-C.I.O. demanded labor law reform, to make it easier for workers to unionize and penalize companies who broke the law. Carter’s response — “Labor Law Reform? For what is that a euphemism?”— was indifferent, if not hostile. Confronting the president’s similar lack of interest in the urban crisis, the chief of staff Hamilton Jordan pleaded at one point: “Mr. President, I do not see how we can continue to alienate key groups of people who were responsible for your election and still maintain our political base.”

Jordan was right: Carter’s base did not hold. In 1980, he won just 49 electoral votes to Mr. Reagan’s 489. Carter’s admirers tend to justify this failure as a kind of achievement by arguing that he’d never wavered from his principles, no matter the cost. The historian Rick Perlstein praised Carter’s appointment of Volcker as “rather heroic and self-sacrificing.”1 Biographer Kai Bird writes that Mr. Carter “was intent on doing the right thing and right away. But there were political consequences to such righteousness” — including the union voters lost between 1976 and 1980. For his part, Mr. Carter recognized that appointing Mr. Volcker had sealed his fate as a one-term president. But he never doubted that that this “tough decision” was “the right one.”

The implication is that maintaining the New Deal coalition, or putting together a new progressive bloc, would have required a species of ethical failure, rather than a new type of politics. This moralization of defeat is misguided, a category in its neat division of virtue and success. The point of politics is to exercise power, which means the point is to win.

“I owe nothing to special interest groups,” Carter claimed. But he did not shun all constituencies with the same rigor.

Even if you find Carter’s anti-political self-presentation admirable — “I owe nothing to special interest groups” — it was disingenuous. He did not shun all constituencies with the same rigor. Carter’s first vault beyond Georgia politics came when he was invited to join the Trilateral Commission, a private group founded by Chase Bank’s David Rockefeller. Carter reportedly studied the Commission’s reports “like a bible,” He appointed many Trilateralists, including Volcker, to key positions. To his admirers, the Volcker appointment exemplifies Mr. Carter’s noble detachment from interest group pressures: he was brave enough to engineer an unpopular recession. But as Eizenstat once stated bluntly, “Volcker was selected because he was the candidate of Wall Street.” Can a decision made in accordance with the wishes of the most powerful people in the country really be described as political courage?

Until 1980, Carter did at least win elections, notably as a representative of the biracial coalition that kept the Georgia Democratic Party competitive even after Lyndon Johnson had supposedly “signed the South away” with his civil rights legislation. Contra LBJ, there was no necessary conflict between virtue and victory. But when he suddenly found himself playing for national (and international) stakes, Carter had neither the focus nor vision to see his hand through. His presidency was a failure by principled standards or by pragmatic ones: He sent the country down the path to neoliberal inequality, only to suffer a crushing defeat by a former actor whose variant of neoliberalism was more outré, more destructive and more politically successful.

Carter’s ascetic defeatism is especially striking in light of his successor’s tactical agility. Reagan, like subsequent Republican presidents, never made the mistake of placing deficit reduction above constituent services. The historical through-line of Democratic fiscal conservatism that began with Carter and Volcker runs through the ’84 Walter Mondale campaign (financed Wall Street deficit hawks like Robert Rubin) onto Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. For a moment, “Bidenomics” seemed to have broken the pattern. But the old-time religion still haunted us, as when former Obama adviser Jason Furman warned that the fight against inflation may require throwing 4 or 5 million Americans out of work. In the wake of the 2024 disaster, the neo-neoliberal formation led by Matt Yglesias has often seemed to work from Carter’s playbook, not only in their deficit hysteria but in the way they combine attacks on weak “special interests” (climate activists, undocumented immigrants, trans people) with defense of special interests which are unpopular but powerful (private equity, AIPAC, health insurance executives).

Ironically, the founders of neoliberalism would later number among the most prominent critics of 21st century American political economy. After Citizens United, Carter referred to his country as “an oligarchy, with unlimited political bribery.” Volcker called it a “plutocracy.” But history is full of people who live long enough to grow uncomfortable in the world they have helped to create. Dwight Eisenhower’s farewell warnings about the military-industrial complex are not less meaningful just because Ike himself had poured hundreds of billions of dollars into the Cold War. If Carter’s late life protests against inequality have helped people trust their own intuition that something is horribly wrong, then the ex-president has rendered a valuable service, to be reckoned alongside his many other admirable contributions.

Let Carter’s personal virtues stand as a rebuke to the rest of our venal and often heartless political class. But his record can tell us little about what kind of collective efforts might have led somewhere else in the 1970s, or might now lead us out from oligarchy.

To Perlstein’s considerable credit, he has disowned this position and offers a highly critical perspective on Volcker in Reaganland, his history of US politics from 1976 to 1980.